Works in Progress

Last Words: Profiles from American History

One of many benefits to my career has been travel to so many intriguing places, both here in North America and also, of course, throughout Europe. Many times, outside the scope of the work I was there to do, I'd run across a personality or oddity that piqued my interest. Once home, I sometimes sketched a profile or short period piece when I had the time. In seeking to find a unifying theme to some of these, I decided to look for "moment of death" scenes that would add significant, dramatic motifs to a story, even when such moments were quiet, such as Stonewall Jackson dying in bed. I found the thread pretty interesting, and often poignant. Mahler, for instance, whose last word was "Mozart"; or John Adams, "Jefferson still lives," even though Jefferson was dead, having passed previously that same day, on a July 4 no less! At last count, I have written almost forty-five such profiles, far too unwieldy for a single book, so I am trimming down the offering and restricting it to North American history as a starter. Here are two of them:

>> Read Last Words: Billy the Kid

>> Read Last Words: Stonewall Jackson

One of many benefits to my career has been travel to so many intriguing places, both here in North America and also, of course, throughout Europe. Many times, outside the scope of the work I was there to do, I'd run across a personality or oddity that piqued my interest. Once home, I sometimes sketched a profile or short period piece when I had the time. In seeking to find a unifying theme to some of these, I decided to look for "moment of death" scenes that would add significant, dramatic motifs to a story, even when such moments were quiet, such as Stonewall Jackson dying in bed. I found the thread pretty interesting, and often poignant. Mahler, for instance, whose last word was "Mozart"; or John Adams, "Jefferson still lives," even though Jefferson was dead, having passed previously that same day, on a July 4 no less! At last count, I have written almost forty-five such profiles, far too unwieldy for a single book, so I am trimming down the offering and restricting it to North American history as a starter. Here are two of them:

>> Read Last Words: Billy the Kid

>> Read Last Words: Stonewall Jackson

Gateway to America: An Informal History of The North Atlantic Coast

This book is about the “neutral space” of North America, and how it became differentiated, separated, and parsed. At the beginning of the European age of discovery, the landmass had no borders. Indigenous peoples roamed the forests and fished the seas, but the fringe areas between them were generally ambiguous, ever changing, and never formal. The great stretch of ocean from Cape Spear in Newfoundland to what later became known as Massachusetts Bay (or the tip of Cape Cod) was no divider, but a trackless highway of sorts that encouraged movement and exploitation. Indentations along the coastline, rivers that could be pursued into a vast and mysterious interior, great bays that offered shelter or refuge from often vicious weather, were haphazardly explored, investigated, often settled and then, just as often, abandoned. Permanent establishments could be few and far between, some foolishly chosen for the worst possible reasons, others just the reverse. European notions of acquisitiveness all played their part as the urge to create (and expand) borders reflected the aggressive policies of kings, statesmen, and soldiers “back home.” Where there were no borders, new settlers tried to create them. Vast, uninhabited wilderness that could not be delineated or legally encumbered, created uneasiness and tension, which often found a release in vicious acts of war. Over the course of two centuries, little dotted lines gradually separated peoples, many of similar racial stock and language. What once had been a universalized expanse of territory became variegated. In the process of all this, the people who were here first, the Amerindians, virtually disappeared. This is a history of change and disquiet ... the North Atlantic Coast.

>> Read Chapter 5: Massachusetts Bay & Its Neighbors

This book is about the “neutral space” of North America, and how it became differentiated, separated, and parsed. At the beginning of the European age of discovery, the landmass had no borders. Indigenous peoples roamed the forests and fished the seas, but the fringe areas between them were generally ambiguous, ever changing, and never formal. The great stretch of ocean from Cape Spear in Newfoundland to what later became known as Massachusetts Bay (or the tip of Cape Cod) was no divider, but a trackless highway of sorts that encouraged movement and exploitation. Indentations along the coastline, rivers that could be pursued into a vast and mysterious interior, great bays that offered shelter or refuge from often vicious weather, were haphazardly explored, investigated, often settled and then, just as often, abandoned. Permanent establishments could be few and far between, some foolishly chosen for the worst possible reasons, others just the reverse. European notions of acquisitiveness all played their part as the urge to create (and expand) borders reflected the aggressive policies of kings, statesmen, and soldiers “back home.” Where there were no borders, new settlers tried to create them. Vast, uninhabited wilderness that could not be delineated or legally encumbered, created uneasiness and tension, which often found a release in vicious acts of war. Over the course of two centuries, little dotted lines gradually separated peoples, many of similar racial stock and language. What once had been a universalized expanse of territory became variegated. In the process of all this, the people who were here first, the Amerindians, virtually disappeared. This is a history of change and disquiet ... the North Atlantic Coast.

>> Read Chapter 5: Massachusetts Bay & Its Neighbors

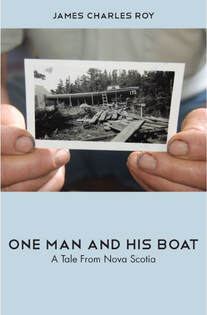

One Man & His Boat: A Tale from Nova Scotia

“Even before he began his writing career, in 1973, James Charles Roy was a savvy traveler and

serious historian. The wonder of his writing career is that he chose to combine those two skills in

a single literary genre—a difficult assignment indeed, which is why so few living writers in the

English language do what Roy does, and does so well. For "One Man, His Boat" the author

takes us through time and space on journeys encompassing Boston's Beacon Hill, Marblehead's

harbor, Newburyport's shoreline, and the coast of rural Nova Scotia. His maritime history

lessons in those locations, especially the latter, emphasize traditional small craft. Regarding the

dual domains of travel and history, Roy gives us personal experience aplenty and meticulous

research, all of it presented in a narrative form that blends oral storytelling with journalistic reporting."

—Paul Lazarus, veteran editor and writer, Professional BoatBuilder Magazine

>> Read Chapter 3: I Find Das Boot

“Even before he began his writing career, in 1973, James Charles Roy was a savvy traveler and

serious historian. The wonder of his writing career is that he chose to combine those two skills in

a single literary genre—a difficult assignment indeed, which is why so few living writers in the

English language do what Roy does, and does so well. For "One Man, His Boat" the author

takes us through time and space on journeys encompassing Boston's Beacon Hill, Marblehead's

harbor, Newburyport's shoreline, and the coast of rural Nova Scotia. His maritime history

lessons in those locations, especially the latter, emphasize traditional small craft. Regarding the

dual domains of travel and history, Roy gives us personal experience aplenty and meticulous

research, all of it presented in a narrative form that blends oral storytelling with journalistic reporting."

—Paul Lazarus, veteran editor and writer, Professional BoatBuilder Magazine

>> Read Chapter 3: I Find Das Boot