Last Words: Billy the Kid

"Quien es? Quien es?" (Who’s that? Who’s that?)

Billy the Kid, before Pat Garrett cut him down, in the dark, with a single shot.

14 July 1881

"Quien es? Quien es?" (Who’s that? Who’s that?)

Billy the Kid, before Pat Garrett cut him down, in the dark, with a single shot.

14 July 1881

Billy the Kid

Billy the Kid

Has there ever been in American history an outlaw more famous than Billy the Kid? Hand in glove with that question is another: has there ever been a greater gap between the historical figure himself and the tidal wave of hysterical prose and cinematic excess that followed him to the grave and beyond? Robert Taylor, Roy Rogers, Audie Murphy, and Paul Newman, among others, all portrayed his character with varying degrees of exaggeration and untruthfulness, and even the famous American composer Aaron Copland threw himself at the legend, writing music for a ballet on “The Kid,” one version of which starred the lean, bare-chested, virile, and handsome dancer Daniel Levans high-stepping in chaps and assorted homoerotic attire. Too bad the real Billy, the only genuine photograph in existence of him anyway, shows a gawky, buck-toothed lad of twenty in a crumpled black hat, tousled shirt, ragged vest, and ill-fitting jacket. The only thing sleek and elegant in this picture is the Kid’s Winchester carbine.

But Billy, unlike the parade of Hollywood actors who mimicked his life, was the real thing, at least in Western terms. Orphaned in Arizona at the age of fourteen, he drifted steadily and inexorably into the aimless life of a meandering cowpoke to whom distinctions between right and wrong, good and evil, usually resolved themselves over who had the fastest draw. When Joe Grant called him a liar and went for his gun, Billy fired off three rounds “right into his chin, could cover them all with a half dollar,” according to one witness. “Joe,” said Billy over the fallen body, “I’ve been there too often for you.”

By 1877 Billy had wandered east into New Mexico, familiarizing himself with the environs of Lincoln County, a far-flung, barely developed outback populated mostly by Hispanic sheepherders and Anglo cattle ranchers. The Pecos River, running due south from near Las Vegas, New Mexico, through Ft. Sumner and Roswell and Seven Rivers to the Rio Grande, watered a landscape so primitive that it reminded early visitors of the Holy Land. “We saw the identical ass on which Jesus rode into Jerusalem,” wrote one observer, while another suggested a new war with Old Mexico, the objective of which would be “to make her take back New Mexico.” It was a last frontier of sorts, a place where, according to one governor, “law was practically a nullity.”

Lincoln itself, the county seat, consisted of a few adobe buildings, one store, and a single street several hundred yards in length. A pair of Irish scoundrels, Jimmy Dolan and Lawrence Murphy, ran the solitary goods store, cheating both their retail customers on day-to-day merchandise as well as the nearby army post with inflated beef contracts. In 1876 an Englishman, John Tunstall, opened a second store diagonally across the street with his Scottish partner, a lawyer named Alexander McSween, seeking their share of the corruption. In fine Celtic fashion, given the pedigree of these principals, this commercial rivalry soon turned to grudge match which, being personal and given the Western predilection for guns and violence, also turned bloody. Tunstall, harassed with a spurious lawsuit and arrest warrant, found himself chased by a posse of deputized Dolan vigilantes, who shot him from his horse. As he lay dying on the ground, a cowboy dismounted and blew in the back of his head with Tunstall’s own pistol. The posse claimed the Englishman had resisted arrest. McSween, five months later, died after an all-day gun battle in Lincoln as he fled his burning store. Five bullets brought him down.

Participating in all these dramatic events was Billy, alias Henry McCarty, Kid Antrim, William Bonney, or just plain “Kid,” who rode with the Tunstall “Regulators.” He too was of Irish extraction, born in New York City to a woman from Limerick who had fled Ireland during the Great Famine of the 1840s. An extremely likeable young man, he was prized by friends for his sunny, open disposition, his sense of gaiety and lively dance steps, the relative loyalty he exhibited to comrades in the feuds which consumed them all. Fluent in Spanish, he was equally prized by Hispanic women, who welcomed him to their bailes (or dance parties) and, it appears, their beds whenever possible. Biological descendants of the Kid still live in New Mexico today. The only thing wrong with Billy, it seems, was a hair-trigger temper and too much masculine testosterone, but in these respects he was no different from other young cowboys of his time.

Nor were his interests in life more varied either, with horses and guns taking precedence. Billy was a superb rider, and practiced gunplay every waking moment. No one ran through more ammunition than the Kid, no one could shoot faster or better, and no one excelled at trick shots or twirling pistols on his fingers, a showy routine that cost many other Western teenagers their lives when they ended up shooting themselves in the stomach by accident.

The aftermath of the Murphy/Dolan and Tunstall/McSween feud (often referred to as the Lincoln County War) was bankruptcy all round. Indeed, when the smoke had settled, only Jimmy Dolan was alive. On a cold winter’s night in Lincoln, an inebriated Dolan, surrounded by cronies, accosted the Widow McSween’s lawyer in the middle of the street. After some crude attempts to cow this individual, one of the group stuck his pistol in the man’s chest and fired. The range was so short that the volatile gunpowder of those days set his clothes on fire, and as the murderers retired they left the dead man’s body smoldering on the ground. Billy, who did not drink, witnessed the killing.

Entering the scene now was a most unlikely participant. Indeed, in the history of the American West, itself so redolent of contrast and irony, the meeting of Billy the Kid, a type of individual we would classify today as a punk, and one of the best-selling authors of all time, Lew Wallace, is an anomaly of almost comic proportions.

Wallace was fifty-one years of age when appointed to the Governorship of New Mexico in 1878. He was a lawyer by training, a military man by temperament, and a political schemer by reputation. He had served in the Mexican War, and rose to the rank of Major General by the Civil War’s final shots in 1864. Only a tardy maneuver during the Battle of Shiloh which had angered Ulysses S. Grant prevented him from reaching greater command status and, thus, greater fame. He served on the trial bench that so miscarried justice in the witch hunt for Abraham Lincoln’s assassins, and he was the presiding judge who condemned Captain Henry Wirtz, Confederate commandant of the Andersonville death camp, to hang. The New Mexico assignment, hardly a plum, he largely accepted out of the need to accelerate his political and financial fortunes. He came this far west hoping to make money in various mining schemes, and hoping even more for enough free time to finish the eighth and final part of his novel Ben Hur. This literary enterprise, when completed, would establish Wallace as the most commercially successful novelist of the nineteenth century. Only the Bible could claim more sales, and the novel remains in print to this day.

What General Wallace actually found when he arrived at the territory’s administrative capital, Sante Fe, was a condition of social and political anarchy, much of it centered in Lincoln County. In some wonderment, he noted the telling statistic that only 150 individuals were registered voters in that huge county, yet outstanding warrants for arrest numbered almost 200 named individuals. Wallace quickly declared a state of insurrection for Lincoln, which enabled him to utilize army troops for the maintenance of civil order, and he issued a general amnesty for crimes committed in 1878 during “the War.” This pardon, however, did not apply to those already under indictment, as Billy was for the murder of Lincoln’s sheriff, a Dolan partisan. Wallace then drove down to Lincoln himself in a horse and buggy, and stayed five weeks to personally oversee the retrieval of law and order.

The Kid, as his friends were quick to point out, was if anything resourceful. Even as a young lad he had had the finely developed knack of squeezing out of tight corners (in one instance, up a chimney flue and out to freedom). At the wizened age of nineteen, he saw the lay of the land and quickly took advantage of Wallace’s arrival. Initiating contact with the Governor, arranging an after-dark rendezvous in Lincoln, Billy entered the room with a pistol in one hand, his Winchester in the other. Getting down to business, the two men made a deal. Billy would testify against Dolan and his men who had murdered the Widow McSween’s lawyer, in return for which Billy would receive the Governor’s pardon on his murder charge. For many and varied reasons, Billy kept his part of the bargain, but Wallace did not. Billy appeared in court as required, gave his testimony as required, but on 13 May 1881, Wallace personally wrote out and signed a death warrant for the Kid. He then left New Mexico, having finished his novel (“I am busy putting in every spare minute copying my new book for publication,” he wrote his wife. “I note your criticism of the march to Golgotha”) and received as his reward for hardship duty in New Mexico the more enviable appointment as ambassador to the Sultan’s Court in Constantinople. “My successor, whoever he be,” Wallace wrote, would soon come to the same conclusion he had regarding the quagmire of New Mexico—“All right, let her drift.”

For Billy, however, sitting in a jail cell in Lincoln, the only drift coming his way was a noose. He was an angry young man at this point, aggrieved at the Governor and appalled that out of fifty men indicted over various misdeeds committed during the War, and many involving murder, he alone had been arrested, convicted, and condemned to suffer the supreme penalty. Not only that, one of his guards, a sadistic bully named John Olinger, was daily taunting him. Loading a double-barreled shotgun with buckshot, he continually took aim at Billy sitting in his cell. “The man that gets one of these loads will feel it,” he said to the Kid.

On 28 April 28 1881, Billy turned the tables. Olinger had escorted five lesser prisoners across the street to a hotel for dinner. Billy asked the remaining guard to take him to the outhouse. Whether a gun was hidden in the privy or not we shall never know, but on returning to his cell on the second floor of the jail, Billy wiggled out of his cuffs and got the jump on his jailer. In the scuffle that followed, Billy put a bullet in him. Olinger, hearing the gunshot, ran back to the jail. Billy stuck his head out the window and yelled, “Hello, old boy,” and put a load of shot from Olinger’s own gun into the deputy’s chest. Billy then shuffled to another window for better aim (his feet were shackled) and put the second barrel into Olinger’s lifeless body. The Kid proceeded to smash the shotgun into pieces, and threw the debris down to ground below. “Take it, damn you, you won’t follow me anymore with that gun.” After haranguing the assembled townspeople for half an hour from the roof, Billy filed off one of his shackle lengths, stuffed the chain in his pants, stole some guns and a horse, and “skinned out.” The Kid was free and entered history, thanks to the Eastern press, as a Western icon.

In retrospect, Billy should have fled over the border into Mexico. Spanish-speaker that he was, he could have roamed there and punched cattle with impunity. But he didn’t. Heading north instead, Billy hid out in Los Portales, a no man’s land of arid waste where cattle rustlers squirreled away their stolen heads. Billy was protected to some degree by his coterie of outlaw friends and Hispanic herders. Every so often he rode into Ft. Sumner to see girlfriends or to dance at bailes. He didn’t exactly feel threatened.

Ft. Sumner, halfway between Sante Fe and Lincoln, was itself beyond the fringe, and thus a magnet for outlaws of all sorts. Formerly an army post established to keep an eye on reservation Navajos evicted from their ancestral lands, the fort had been sold to the Maxwell family in 1871 after the Navajos had been allowed to return home. The ramshackle fort turned into a squatters’ heaven as the Maxwells moved their ranch hands, mostly Hispanics, into the various barracks, and let barkeeps and store owners into other disused buildings. Beaver Smith’s saloon was a typical such establishment. Old Beaver, an incorrigible gossip whose ear had been branded one night by cowboys looking for fun, ran a rough-and-ready kind of place where gambling, bailes, and whiskey provided the only entertainment for miles around. Lawmen were not particularly welcome at Beaver’s or anywhere else in Ft. Sumner.

But Billy, unlike the parade of Hollywood actors who mimicked his life, was the real thing, at least in Western terms. Orphaned in Arizona at the age of fourteen, he drifted steadily and inexorably into the aimless life of a meandering cowpoke to whom distinctions between right and wrong, good and evil, usually resolved themselves over who had the fastest draw. When Joe Grant called him a liar and went for his gun, Billy fired off three rounds “right into his chin, could cover them all with a half dollar,” according to one witness. “Joe,” said Billy over the fallen body, “I’ve been there too often for you.”

By 1877 Billy had wandered east into New Mexico, familiarizing himself with the environs of Lincoln County, a far-flung, barely developed outback populated mostly by Hispanic sheepherders and Anglo cattle ranchers. The Pecos River, running due south from near Las Vegas, New Mexico, through Ft. Sumner and Roswell and Seven Rivers to the Rio Grande, watered a landscape so primitive that it reminded early visitors of the Holy Land. “We saw the identical ass on which Jesus rode into Jerusalem,” wrote one observer, while another suggested a new war with Old Mexico, the objective of which would be “to make her take back New Mexico.” It was a last frontier of sorts, a place where, according to one governor, “law was practically a nullity.”

Lincoln itself, the county seat, consisted of a few adobe buildings, one store, and a single street several hundred yards in length. A pair of Irish scoundrels, Jimmy Dolan and Lawrence Murphy, ran the solitary goods store, cheating both their retail customers on day-to-day merchandise as well as the nearby army post with inflated beef contracts. In 1876 an Englishman, John Tunstall, opened a second store diagonally across the street with his Scottish partner, a lawyer named Alexander McSween, seeking their share of the corruption. In fine Celtic fashion, given the pedigree of these principals, this commercial rivalry soon turned to grudge match which, being personal and given the Western predilection for guns and violence, also turned bloody. Tunstall, harassed with a spurious lawsuit and arrest warrant, found himself chased by a posse of deputized Dolan vigilantes, who shot him from his horse. As he lay dying on the ground, a cowboy dismounted and blew in the back of his head with Tunstall’s own pistol. The posse claimed the Englishman had resisted arrest. McSween, five months later, died after an all-day gun battle in Lincoln as he fled his burning store. Five bullets brought him down.

Participating in all these dramatic events was Billy, alias Henry McCarty, Kid Antrim, William Bonney, or just plain “Kid,” who rode with the Tunstall “Regulators.” He too was of Irish extraction, born in New York City to a woman from Limerick who had fled Ireland during the Great Famine of the 1840s. An extremely likeable young man, he was prized by friends for his sunny, open disposition, his sense of gaiety and lively dance steps, the relative loyalty he exhibited to comrades in the feuds which consumed them all. Fluent in Spanish, he was equally prized by Hispanic women, who welcomed him to their bailes (or dance parties) and, it appears, their beds whenever possible. Biological descendants of the Kid still live in New Mexico today. The only thing wrong with Billy, it seems, was a hair-trigger temper and too much masculine testosterone, but in these respects he was no different from other young cowboys of his time.

Nor were his interests in life more varied either, with horses and guns taking precedence. Billy was a superb rider, and practiced gunplay every waking moment. No one ran through more ammunition than the Kid, no one could shoot faster or better, and no one excelled at trick shots or twirling pistols on his fingers, a showy routine that cost many other Western teenagers their lives when they ended up shooting themselves in the stomach by accident.

The aftermath of the Murphy/Dolan and Tunstall/McSween feud (often referred to as the Lincoln County War) was bankruptcy all round. Indeed, when the smoke had settled, only Jimmy Dolan was alive. On a cold winter’s night in Lincoln, an inebriated Dolan, surrounded by cronies, accosted the Widow McSween’s lawyer in the middle of the street. After some crude attempts to cow this individual, one of the group stuck his pistol in the man’s chest and fired. The range was so short that the volatile gunpowder of those days set his clothes on fire, and as the murderers retired they left the dead man’s body smoldering on the ground. Billy, who did not drink, witnessed the killing.

Entering the scene now was a most unlikely participant. Indeed, in the history of the American West, itself so redolent of contrast and irony, the meeting of Billy the Kid, a type of individual we would classify today as a punk, and one of the best-selling authors of all time, Lew Wallace, is an anomaly of almost comic proportions.

Wallace was fifty-one years of age when appointed to the Governorship of New Mexico in 1878. He was a lawyer by training, a military man by temperament, and a political schemer by reputation. He had served in the Mexican War, and rose to the rank of Major General by the Civil War’s final shots in 1864. Only a tardy maneuver during the Battle of Shiloh which had angered Ulysses S. Grant prevented him from reaching greater command status and, thus, greater fame. He served on the trial bench that so miscarried justice in the witch hunt for Abraham Lincoln’s assassins, and he was the presiding judge who condemned Captain Henry Wirtz, Confederate commandant of the Andersonville death camp, to hang. The New Mexico assignment, hardly a plum, he largely accepted out of the need to accelerate his political and financial fortunes. He came this far west hoping to make money in various mining schemes, and hoping even more for enough free time to finish the eighth and final part of his novel Ben Hur. This literary enterprise, when completed, would establish Wallace as the most commercially successful novelist of the nineteenth century. Only the Bible could claim more sales, and the novel remains in print to this day.

What General Wallace actually found when he arrived at the territory’s administrative capital, Sante Fe, was a condition of social and political anarchy, much of it centered in Lincoln County. In some wonderment, he noted the telling statistic that only 150 individuals were registered voters in that huge county, yet outstanding warrants for arrest numbered almost 200 named individuals. Wallace quickly declared a state of insurrection for Lincoln, which enabled him to utilize army troops for the maintenance of civil order, and he issued a general amnesty for crimes committed in 1878 during “the War.” This pardon, however, did not apply to those already under indictment, as Billy was for the murder of Lincoln’s sheriff, a Dolan partisan. Wallace then drove down to Lincoln himself in a horse and buggy, and stayed five weeks to personally oversee the retrieval of law and order.

The Kid, as his friends were quick to point out, was if anything resourceful. Even as a young lad he had had the finely developed knack of squeezing out of tight corners (in one instance, up a chimney flue and out to freedom). At the wizened age of nineteen, he saw the lay of the land and quickly took advantage of Wallace’s arrival. Initiating contact with the Governor, arranging an after-dark rendezvous in Lincoln, Billy entered the room with a pistol in one hand, his Winchester in the other. Getting down to business, the two men made a deal. Billy would testify against Dolan and his men who had murdered the Widow McSween’s lawyer, in return for which Billy would receive the Governor’s pardon on his murder charge. For many and varied reasons, Billy kept his part of the bargain, but Wallace did not. Billy appeared in court as required, gave his testimony as required, but on 13 May 1881, Wallace personally wrote out and signed a death warrant for the Kid. He then left New Mexico, having finished his novel (“I am busy putting in every spare minute copying my new book for publication,” he wrote his wife. “I note your criticism of the march to Golgotha”) and received as his reward for hardship duty in New Mexico the more enviable appointment as ambassador to the Sultan’s Court in Constantinople. “My successor, whoever he be,” Wallace wrote, would soon come to the same conclusion he had regarding the quagmire of New Mexico—“All right, let her drift.”

For Billy, however, sitting in a jail cell in Lincoln, the only drift coming his way was a noose. He was an angry young man at this point, aggrieved at the Governor and appalled that out of fifty men indicted over various misdeeds committed during the War, and many involving murder, he alone had been arrested, convicted, and condemned to suffer the supreme penalty. Not only that, one of his guards, a sadistic bully named John Olinger, was daily taunting him. Loading a double-barreled shotgun with buckshot, he continually took aim at Billy sitting in his cell. “The man that gets one of these loads will feel it,” he said to the Kid.

On 28 April 28 1881, Billy turned the tables. Olinger had escorted five lesser prisoners across the street to a hotel for dinner. Billy asked the remaining guard to take him to the outhouse. Whether a gun was hidden in the privy or not we shall never know, but on returning to his cell on the second floor of the jail, Billy wiggled out of his cuffs and got the jump on his jailer. In the scuffle that followed, Billy put a bullet in him. Olinger, hearing the gunshot, ran back to the jail. Billy stuck his head out the window and yelled, “Hello, old boy,” and put a load of shot from Olinger’s own gun into the deputy’s chest. Billy then shuffled to another window for better aim (his feet were shackled) and put the second barrel into Olinger’s lifeless body. The Kid proceeded to smash the shotgun into pieces, and threw the debris down to ground below. “Take it, damn you, you won’t follow me anymore with that gun.” After haranguing the assembled townspeople for half an hour from the roof, Billy filed off one of his shackle lengths, stuffed the chain in his pants, stole some guns and a horse, and “skinned out.” The Kid was free and entered history, thanks to the Eastern press, as a Western icon.

In retrospect, Billy should have fled over the border into Mexico. Spanish-speaker that he was, he could have roamed there and punched cattle with impunity. But he didn’t. Heading north instead, Billy hid out in Los Portales, a no man’s land of arid waste where cattle rustlers squirreled away their stolen heads. Billy was protected to some degree by his coterie of outlaw friends and Hispanic herders. Every so often he rode into Ft. Sumner to see girlfriends or to dance at bailes. He didn’t exactly feel threatened.

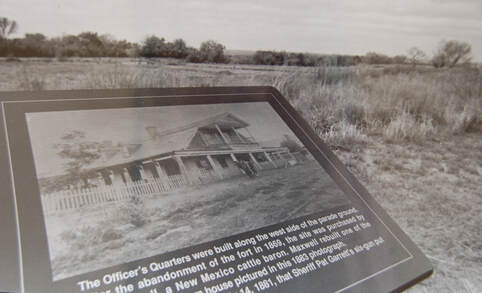

Ft. Sumner, halfway between Sante Fe and Lincoln, was itself beyond the fringe, and thus a magnet for outlaws of all sorts. Formerly an army post established to keep an eye on reservation Navajos evicted from their ancestral lands, the fort had been sold to the Maxwell family in 1871 after the Navajos had been allowed to return home. The ramshackle fort turned into a squatters’ heaven as the Maxwells moved their ranch hands, mostly Hispanics, into the various barracks, and let barkeeps and store owners into other disused buildings. Beaver Smith’s saloon was a typical such establishment. Old Beaver, an incorrigible gossip whose ear had been branded one night by cowboys looking for fun, ran a rough-and-ready kind of place where gambling, bailes, and whiskey provided the only entertainment for miles around. Lawmen were not particularly welcome at Beaver’s or anywhere else in Ft. Sumner.

The Site of "Maxell's House" Ft. Sumner, New Mexico

The Site of "Maxell's House" Ft. Sumner, New Mexico

Pat Garrett, sheriff of Lincoln County, was a possible exception. Married twice to Hispanic women, and once a bartender at Beaver Smith’s, he had a good ear to the ground and plenty of inside knowledge. He knew, or suspected, that Billy was hanging around the neighborhood, and he was very interested in the $500 reward.

Garrett had captured Billy once before (and collected an earlier reward) in typical Wild West fashion. Laying a trap in Ft. Sumner, he and his men had opened fire without warning on Billy’s gang as they entered the settlement one snowy night (Garrett claimed he yelled “Halt,” but no one believed him.). An outlaw fell from his horse but the others slipped away. Garrett dragged the dying man into a hut and by the fire, then proceeded to play poker with his deputies to the background of a death rattle and coughing. “God damn you, Garrett,” muttered the bandit. “I wouldn’t talk that way, Tom,” the sheriff replied, “You’re going to die in a few minutes.” He continued the card game. Three days later, the posse had tracked Billy and his men to a stone cabin. When one of the gang came out to relieve himself in the morning, Garrett cut him down with a single shot. For good measure he shot one of their horses too, blocking the doorway to prevent a mad dash on the part of those inside. After a stand-off of several hours, Billy surrendered.

Now Garrett was after the Kid again. He and two deputies staked out the old fort’s parade grounds in the darkness of a July night. They overheard voices, saw a man and woman together out in the orchard, watched them separate and go back to the fort. Was it Billy the Kid with one of his amours? Garrett positioned his deputies outside and entered the bedroom of Peter Maxwell, who was asleep, to find out.

Indeed, it had been Billy. Bunking in with a Mexican friend, the Kid partially undressed, then decided he felt like a steak and coffee. Taking a butcher’s knife in one hand and, allegedly, a pistol in the other, he walked in his stocking feet to Peter Maxwell’s porch, where a shank of beef was hanging to cure. Bumping into the deputies, a startled Billy backed into Maxwell’s bedroom. “Who are those fellows outside?” he whispered to Maxwell. Maxwell, barely awake, muttered to Garrett, “That’s him!” Billy, now moving away from Maxwell’s bed, said “Quien es? Quien es?” (“Who’s that? Who’s that?”), upon which Garrett shot him dead. A contemporary newspaper account reported that as Billy dropped to the floor, “a strong odor of brimstone filled the air,” and that Satan (presumably) was heard to say, “This is my meat.”

As for Maxwell, terrified as well he might be, he bolted from the room with an equally unnerved Garrett. Both were lucky the deputies outside didn’t shoot them down in panic. Rumors persist that no one dared re-enter the bedroom. Garrett, in his self-serving book on the affair, claims he went in to check out his handiwork, but Hispanic accounts contradict this version. An old Navaho woman, with a candle in hand, was evidently the first to survey the scene. “My little boy is dead,” she cried, then came out to blister Garrett as a “piss-pot” and a “sonafabitch.” As word spread through the compound and a crowd gathered, Garrett and his deputies barricaded themselves in a room and stood guard all night.

Confusion also surrounds the “official” inquest, as rumors still persist that a first inquiry, held in the bedroom with Billy’s body still lying on the floor, implied that Garrett had essentially executed Billy. As the Widow McSween later put it, “Every man Garrett ever killed was shot without warning.” Garrett apparently refused to accept such an ambivalent verdict, however, and after much persuasion the inquest returned a more judicious finding of “justifiable homicide.”

The question remains, of course, was Billy ever armed? Some critics question if the Kid would have ever hesitated opening fire as he so obviously did that fateful night. Billy was quick as a cat and ruthless when cornered. If he’d had a gun in his hand, they argue, he would have started shooting almost as a reflex, whether Peter Maxwell was in the line of fire or not. Could Garrett have planted the gun later found next to the body? History will never have an answer to that question.

Garrett had captured Billy once before (and collected an earlier reward) in typical Wild West fashion. Laying a trap in Ft. Sumner, he and his men had opened fire without warning on Billy’s gang as they entered the settlement one snowy night (Garrett claimed he yelled “Halt,” but no one believed him.). An outlaw fell from his horse but the others slipped away. Garrett dragged the dying man into a hut and by the fire, then proceeded to play poker with his deputies to the background of a death rattle and coughing. “God damn you, Garrett,” muttered the bandit. “I wouldn’t talk that way, Tom,” the sheriff replied, “You’re going to die in a few minutes.” He continued the card game. Three days later, the posse had tracked Billy and his men to a stone cabin. When one of the gang came out to relieve himself in the morning, Garrett cut him down with a single shot. For good measure he shot one of their horses too, blocking the doorway to prevent a mad dash on the part of those inside. After a stand-off of several hours, Billy surrendered.

Now Garrett was after the Kid again. He and two deputies staked out the old fort’s parade grounds in the darkness of a July night. They overheard voices, saw a man and woman together out in the orchard, watched them separate and go back to the fort. Was it Billy the Kid with one of his amours? Garrett positioned his deputies outside and entered the bedroom of Peter Maxwell, who was asleep, to find out.

Indeed, it had been Billy. Bunking in with a Mexican friend, the Kid partially undressed, then decided he felt like a steak and coffee. Taking a butcher’s knife in one hand and, allegedly, a pistol in the other, he walked in his stocking feet to Peter Maxwell’s porch, where a shank of beef was hanging to cure. Bumping into the deputies, a startled Billy backed into Maxwell’s bedroom. “Who are those fellows outside?” he whispered to Maxwell. Maxwell, barely awake, muttered to Garrett, “That’s him!” Billy, now moving away from Maxwell’s bed, said “Quien es? Quien es?” (“Who’s that? Who’s that?”), upon which Garrett shot him dead. A contemporary newspaper account reported that as Billy dropped to the floor, “a strong odor of brimstone filled the air,” and that Satan (presumably) was heard to say, “This is my meat.”

As for Maxwell, terrified as well he might be, he bolted from the room with an equally unnerved Garrett. Both were lucky the deputies outside didn’t shoot them down in panic. Rumors persist that no one dared re-enter the bedroom. Garrett, in his self-serving book on the affair, claims he went in to check out his handiwork, but Hispanic accounts contradict this version. An old Navaho woman, with a candle in hand, was evidently the first to survey the scene. “My little boy is dead,” she cried, then came out to blister Garrett as a “piss-pot” and a “sonafabitch.” As word spread through the compound and a crowd gathered, Garrett and his deputies barricaded themselves in a room and stood guard all night.

Confusion also surrounds the “official” inquest, as rumors still persist that a first inquiry, held in the bedroom with Billy’s body still lying on the floor, implied that Garrett had essentially executed Billy. As the Widow McSween later put it, “Every man Garrett ever killed was shot without warning.” Garrett apparently refused to accept such an ambivalent verdict, however, and after much persuasion the inquest returned a more judicious finding of “justifiable homicide.”

The question remains, of course, was Billy ever armed? Some critics question if the Kid would have ever hesitated opening fire as he so obviously did that fateful night. Billy was quick as a cat and ruthless when cornered. If he’d had a gun in his hand, they argue, he would have started shooting almost as a reflex, whether Peter Maxwell was in the line of fire or not. Could Garrett have planted the gun later found next to the body? History will never have an answer to that question.

Billy's Grave

Billy's Grave

Ft. Sumner today is mostly gone. The front range of barracks have been rebuilt and turned into a small museum, but all the rest has been devoured by a century’s worth of unrelenting weather. The Pecos River, for much of the year a dry, sun-parched, meandering ditch, has been known to transform itself into raging tidal waves of water. In 1941 the entire fort, and the adjoining graveyard where Billy was buried, stood under four and a half feet of water. Many graves reopened and released their grisly contents but such was not the case, evidently, with the Kid’s. The problem with his site was the grave marker, stolen in 1950 and not recovered for twenty-six years until it turned up in Granbury, Texas. In 1981, someone jacked it again, but this time it took only four days to recover in Huntington Beach, California. De Baca County Sheriff Big John McBride personally brought it home, and county officials arranged the current architectural treatment. The Kid’s grave was covered in a cement slab, the marker reset in mortar and shackled in padlocked iron bars. The whole site was then covered by a metal cage, the doors of which are chained and again padlocked. The Kid, who could break any jail, isn’t going anywhere now.

As for Pat Garrett, he had an argument with a Hispanic goat herder. After cursing the fellow out, Garrett, rifle in hand, turned around, unzipped his trousers, and proceeded to urinate. He was shot from behind in the rear of his head; after falling down, he was shot again in the back. His assailant, when tried, was acquitted on grounds of self-defense. He had been defended, skillfully it appears, by one Albert Bacon Fall, who later became one of the first two senators from New Mexico when the territory achieved statehood. New Mexico being what it is, a large state with few people, lives and interests intersect continuously. Fall bought out the Widow McSween’s ranch, of all people, and later became Secretary of the Interior under President Harding. He went to jail in 1931 as a mastermind of the Teapot Dome Scandal.

As for Pat Garrett, he had an argument with a Hispanic goat herder. After cursing the fellow out, Garrett, rifle in hand, turned around, unzipped his trousers, and proceeded to urinate. He was shot from behind in the rear of his head; after falling down, he was shot again in the back. His assailant, when tried, was acquitted on grounds of self-defense. He had been defended, skillfully it appears, by one Albert Bacon Fall, who later became one of the first two senators from New Mexico when the territory achieved statehood. New Mexico being what it is, a large state with few people, lives and interests intersect continuously. Fall bought out the Widow McSween’s ranch, of all people, and later became Secretary of the Interior under President Harding. He went to jail in 1931 as a mastermind of the Teapot Dome Scandal.