When the Train Left the Station

Chapter 6: Dockery’s Farm

“You asking’ me for my all-time favorite singer? That was Charlie Patton.” —Howlin’ Wolf

Restored service station, Dockery’s Farm

Restored service station, Dockery’s Farm

People talk all the time about the romance of the blues. It’s a vicarious daydream, to say the least: hopping freight trains, drinking moonshine whiskey, dancing away all those hot Saturday nights, getting up hung-over the next morning and maybe hearing some old-time religion at the plantation chapel; then, inevitably, the bell ringing before dawn on Monday morning, starting yet another hard week working away for “the man,” all the while bemoaning your fate and worrying that some guy is messing with your woman (commonly referred to as “kicking in another man’s stall”). What else was a poor boy to do except sing the blues? Having said all that, I’m pretty sure of one thing: this all sounds better than actually living it.

There are certainly other fantasias that, in all probability, attract more people than the blues, and have more exciting physical remnants to recreate a proper atmospheric milieu. Tolkien experts can go to England and see superb countryside and real-life castles; it doesn’t take much imagination to see a few hobbits here and there. Star War freaks can go to Cape Canaveral or, strangely, the remote offshore island of Skellig Michael in Ireland to revisit with Luke Skywalker in The Force Awakens. Blues enthusiasts have the songs, but to be honest, not much else except enormous vistas of drab and empty fields.

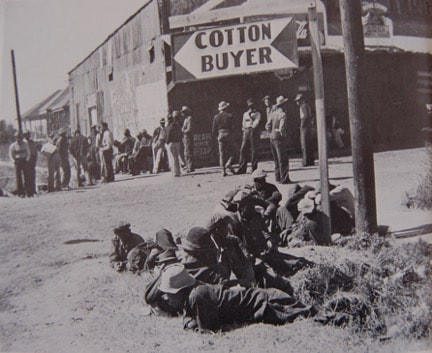

Dockery’s Farm, however, is an A-List attraction on the blues trail, there is no question about that. It’s easy to find, as is everything in the flat, sometimes grid-like layout of the Mississippi Delta. If you’re driving north from Greenwood towards Clarksdale, you head west after sixteen miles or so onto Route 8, and in a few minutes you’ll come to the Dockery Service Station. This immaculately restored general store, full of bright red Coca-Cola signs and two pumps (Lion Gas) probably should be in the Smithsonian as an ode to rural Southern life. What it does not do is remind me of Dorothea Lange’s undeniably authentic photograph of pretty much the same thing, taken in 1939. Down the road from this place is Dockery’s Farm, which is impossible to miss.

Dockery’s is named after its founder, William O. (“Will”) Dockery. His name, and that of his son and successor, Joe Rice, with their dates, are boldly painted on one of the remaining farm buildings. It stands in the very center of the once vibrant working complex, which included a cotton gin, a commissary building (only the foundation of that survives), and many other sheds and outbuildings. The whole place is manicured clean, and was deserted when we came by. It does not give a visitor the impression that he or she is walking around through a “dark feudal community,” even though that’s what Dockery’s was. If you venture farther in from the road, you come to a bridge over the Sunflower River that led to the day-laborers’ quarters, all now overgrown ruins. Along the way, when you press a button, you’ll hear a scratchy performance of a blues song, performed by the man who put this place on a larger map than ever Will Dockery did, the inimitable Charlie Patton.

There are certainly other fantasias that, in all probability, attract more people than the blues, and have more exciting physical remnants to recreate a proper atmospheric milieu. Tolkien experts can go to England and see superb countryside and real-life castles; it doesn’t take much imagination to see a few hobbits here and there. Star War freaks can go to Cape Canaveral or, strangely, the remote offshore island of Skellig Michael in Ireland to revisit with Luke Skywalker in The Force Awakens. Blues enthusiasts have the songs, but to be honest, not much else except enormous vistas of drab and empty fields.

Dockery’s Farm, however, is an A-List attraction on the blues trail, there is no question about that. It’s easy to find, as is everything in the flat, sometimes grid-like layout of the Mississippi Delta. If you’re driving north from Greenwood towards Clarksdale, you head west after sixteen miles or so onto Route 8, and in a few minutes you’ll come to the Dockery Service Station. This immaculately restored general store, full of bright red Coca-Cola signs and two pumps (Lion Gas) probably should be in the Smithsonian as an ode to rural Southern life. What it does not do is remind me of Dorothea Lange’s undeniably authentic photograph of pretty much the same thing, taken in 1939. Down the road from this place is Dockery’s Farm, which is impossible to miss.

Dockery’s is named after its founder, William O. (“Will”) Dockery. His name, and that of his son and successor, Joe Rice, with their dates, are boldly painted on one of the remaining farm buildings. It stands in the very center of the once vibrant working complex, which included a cotton gin, a commissary building (only the foundation of that survives), and many other sheds and outbuildings. The whole place is manicured clean, and was deserted when we came by. It does not give a visitor the impression that he or she is walking around through a “dark feudal community,” even though that’s what Dockery’s was. If you venture farther in from the road, you come to a bridge over the Sunflower River that led to the day-laborers’ quarters, all now overgrown ruins. Along the way, when you press a button, you’ll hear a scratchy performance of a blues song, performed by the man who put this place on a larger map than ever Will Dockery did, the inimitable Charlie Patton.

Gas pumps and general store, by Dorothea Lange, 1936

Gas pumps and general store, by Dorothea Lange, 1936

Among enthusiasts who know a lot more about the blues than I do, this guy is the king. A superb guitarist, distinctive vocalist, spellbinding entertainer, and thorough-going scoundrel, he is the embodiment of blues mythology. If anyone “lived the life,” Patton did, and unlike a Robert Johnson, he left a considerable body of recorded work behind, some fifty-four songs, and a more authentic trail of reminiscences from friends and acquaintances, having lived (as just one explanation) more than sixteen years longer than Johnson. How he managed to do that is difficult to explain, given the rough and tumble times he lived through. They are probably best expressed in a tune called “Sloppy Drunk Blues,” whose major theme is pretty straightforward: “I’d rather be sloppy drunk than anything I know.”

Charlie Patton lived in and around Dockery for some thirty intermittent years, and probably longer than that on a come-and-go basis. It was the center of his nomadic lifestyle, one that he often left, whether voluntarily or not, but where he usually turned up again a few weeks or months or even years later, rather like a bad penny. His domiciles were generally scattered round the place, depending on his woman of the moment. At one time he lived “on” the farm, but fifteen miles from its center, which gives some idea as to the extent of Will Dockery’s holdings (some forty square miles).

Some writers have called Dockery’s the birthplace of the blues, not only because of the Patton association, but the long list of other blues artists who lived here or were known to have passed through, people like Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Brown, Roebuck “Pops” Staples (the gospel and R&B great). The main attraction, however, is Patton.

His parents and their children moved here for work when he was perhaps only three years old (his exact date of birth remains hotly debated). His father was an entrepreneurial man who also knew how to read, and later in life he owned land of his own and ran a country store. But their early years on Dockery’s were all about manual labor, and Charlie, like his siblings, must have spent his share of time either in the fields or sweating it out in some aspect of farm chores. The bigger the family, the better: it meant more hands on the job. One thing’s for sure, Charlie didn’t like it. He was more interested in loafing about and learning how to play guitar. It is said that his father attempted to discourage his musical inclinations by beating it out of him but again, there is no certain proof of this.

Nor do we know, beyond generalities, who the boy turned to when it came to picking up the finer points of guitar playing. There were one or two musicians on the plantation whose names we have, and they may have had some influence. And who knows how many drifters and hobos wandered through the place, especially after Dockery laid tracks and built a train depot on his property to ship cotton bales to Rosedale, on the Mississippi. As W. C. Handy noted, hobos with guitars were a common sight in the Delta (he called them “footloose bards”). We may presume, I think, that Charlie was in most ways self-taught. He was so original and one-of-a kind whom others would seek to copy, that it makes sense to think of him as being at the head of the line who needed only a jump start to get going. One cannot say too much more of anything about his childhood than that, however unsatisfactory this seems.

Charlie Patton came of age at a pivotal point in the Delta’s development, the moment when thousands of acres were being transformed from primeval swampland into some of the most productive agricultural land in the world, so rich in potential that one real estate speculator compared it to the Nile Delta of Egypt (another called it the equivalent to Saudi Arabia with its untold millions of gallons of oil). The contrast between the entrepreneurial zeal and attendant profits that a Will Dockery forced from the land, using labor like Charlie Patton’s, and the never-ending financial quagmire that engulfed nearly all the Negroes on his place, represent the two extremes of a unique Delta history that are the origins, I believe, of the blues.

Will Dockery

Dockery, born in 1865, was twenty-five years old when he saddled a horse and went exploring east of a crossroads known as Cleveland (five shops and several saloons) along the meandering Sunflower River. He was a man of ambition, seeking his fortune with a modest nest egg of $1,000 from an aunt. A college graduate (Ole Miss) with some business experience keeping books and running a commissary, Dockery knew something about agriculture as well, his family’s business. As he entered what was, in fact, a wilderness, he kept his mind focused on the one outstanding impression that he noted right away: “the land was as rich as cream.” The problem was getting at it.

The Delta landscape he explored was essentially an alluvial swamp, most of it in perpetual forest shade. He spent his days crossing streams, losing leggings, watching out for snakes, camping in the open, his company a flood of malaria-carrying mosquitoes. His first purchase of a few hundred acres would be followed, over time, by another 10,000. Lumber companies had been the first exploiters on the scene. Virgin land could be bought for next to nothing, Dockery noting that he had seen multi-acre lots being swapped for a cow or, in another instance, for a Winchester rifle. Moving camps of axe-wielding woodsmen took their pick of choice varieties (Memphis would soon become one of the major lumber capitals in the country). One Mary Hamilton, whose diaries, exceptionally well written, are invaluable guides through this period, describes in detail the life she and her husband led hacking their way into the Mississippi interior, leaving behind Missouri and Arkansas forests that had already been mown through. Crossing the Mississippi River by boat in 1897, Hamilton was amazed at what greeted her eyes. “Standing on the boat and looking at the bank, I could see everything but a road. Timber of all kinds stood so close together as almost to shut out all daylight; tall cane, blackberry vines, and a tangled mass of all kinds of vines wove around and all over it.” Moving east, they crossed the Sunflower River (“I think I was the first white woman … coming into this country to live,” she noted), sleeping in shanty huts and camps before building more substantial abodes. “Standing at my house it looked like the Garden of Eden I imagined. How I did love it.” She seemed unaware of the contrast implied in her next sentence, “all the woods full of animals and birds, and full of workmen too. We could hear them chopping and sawing and trees falling.” Hamilton had the pioneer spirit. In order to create something, most allurements of the Garden of Eden had to go.

Charlie Patton lived in and around Dockery for some thirty intermittent years, and probably longer than that on a come-and-go basis. It was the center of his nomadic lifestyle, one that he often left, whether voluntarily or not, but where he usually turned up again a few weeks or months or even years later, rather like a bad penny. His domiciles were generally scattered round the place, depending on his woman of the moment. At one time he lived “on” the farm, but fifteen miles from its center, which gives some idea as to the extent of Will Dockery’s holdings (some forty square miles).

Some writers have called Dockery’s the birthplace of the blues, not only because of the Patton association, but the long list of other blues artists who lived here or were known to have passed through, people like Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Brown, Roebuck “Pops” Staples (the gospel and R&B great). The main attraction, however, is Patton.

His parents and their children moved here for work when he was perhaps only three years old (his exact date of birth remains hotly debated). His father was an entrepreneurial man who also knew how to read, and later in life he owned land of his own and ran a country store. But their early years on Dockery’s were all about manual labor, and Charlie, like his siblings, must have spent his share of time either in the fields or sweating it out in some aspect of farm chores. The bigger the family, the better: it meant more hands on the job. One thing’s for sure, Charlie didn’t like it. He was more interested in loafing about and learning how to play guitar. It is said that his father attempted to discourage his musical inclinations by beating it out of him but again, there is no certain proof of this.

Nor do we know, beyond generalities, who the boy turned to when it came to picking up the finer points of guitar playing. There were one or two musicians on the plantation whose names we have, and they may have had some influence. And who knows how many drifters and hobos wandered through the place, especially after Dockery laid tracks and built a train depot on his property to ship cotton bales to Rosedale, on the Mississippi. As W. C. Handy noted, hobos with guitars were a common sight in the Delta (he called them “footloose bards”). We may presume, I think, that Charlie was in most ways self-taught. He was so original and one-of-a kind whom others would seek to copy, that it makes sense to think of him as being at the head of the line who needed only a jump start to get going. One cannot say too much more of anything about his childhood than that, however unsatisfactory this seems.

Charlie Patton came of age at a pivotal point in the Delta’s development, the moment when thousands of acres were being transformed from primeval swampland into some of the most productive agricultural land in the world, so rich in potential that one real estate speculator compared it to the Nile Delta of Egypt (another called it the equivalent to Saudi Arabia with its untold millions of gallons of oil). The contrast between the entrepreneurial zeal and attendant profits that a Will Dockery forced from the land, using labor like Charlie Patton’s, and the never-ending financial quagmire that engulfed nearly all the Negroes on his place, represent the two extremes of a unique Delta history that are the origins, I believe, of the blues.

Will Dockery

Dockery, born in 1865, was twenty-five years old when he saddled a horse and went exploring east of a crossroads known as Cleveland (five shops and several saloons) along the meandering Sunflower River. He was a man of ambition, seeking his fortune with a modest nest egg of $1,000 from an aunt. A college graduate (Ole Miss) with some business experience keeping books and running a commissary, Dockery knew something about agriculture as well, his family’s business. As he entered what was, in fact, a wilderness, he kept his mind focused on the one outstanding impression that he noted right away: “the land was as rich as cream.” The problem was getting at it.

The Delta landscape he explored was essentially an alluvial swamp, most of it in perpetual forest shade. He spent his days crossing streams, losing leggings, watching out for snakes, camping in the open, his company a flood of malaria-carrying mosquitoes. His first purchase of a few hundred acres would be followed, over time, by another 10,000. Lumber companies had been the first exploiters on the scene. Virgin land could be bought for next to nothing, Dockery noting that he had seen multi-acre lots being swapped for a cow or, in another instance, for a Winchester rifle. Moving camps of axe-wielding woodsmen took their pick of choice varieties (Memphis would soon become one of the major lumber capitals in the country). One Mary Hamilton, whose diaries, exceptionally well written, are invaluable guides through this period, describes in detail the life she and her husband led hacking their way into the Mississippi interior, leaving behind Missouri and Arkansas forests that had already been mown through. Crossing the Mississippi River by boat in 1897, Hamilton was amazed at what greeted her eyes. “Standing on the boat and looking at the bank, I could see everything but a road. Timber of all kinds stood so close together as almost to shut out all daylight; tall cane, blackberry vines, and a tangled mass of all kinds of vines wove around and all over it.” Moving east, they crossed the Sunflower River (“I think I was the first white woman … coming into this country to live,” she noted), sleeping in shanty huts and camps before building more substantial abodes. “Standing at my house it looked like the Garden of Eden I imagined. How I did love it.” She seemed unaware of the contrast implied in her next sentence, “all the woods full of animals and birds, and full of workmen too. We could hear them chopping and sawing and trees falling.” Hamilton had the pioneer spirit. In order to create something, most allurements of the Garden of Eden had to go.

Dockery’s Farm, sanitized version, 2014

Dockery’s Farm, sanitized version, 2014

More capital-heavy investors followed, mostly railroad interests who purchased woodlots for $5 an acre, clearcut the whole swath, hauled out the trees by rail, then sold the land for 10 cents per acre to anyone foolish enough to buy it.[1] This was the classic get-rich-quick scheme of things so typical of the Industrial Age. Dockery’s plan was a bit more far minded. He too harvested lumber from his properties, but the main goal was to plant cotton.

A Will Dockery was desperate for men willing to work. Clearing his farm was a backbreaking and expensive venture. The portions of Dockery’s wilderness that were not under water when he first saw it were covered with cane bush and undergrowth that often stood over fifteen feet high. Land had to be drained, trees cut, stumps pulled out, and cotton seeds put to ground as quickly as possible. In his haste, many trees were left in situ, slashed of bark around their girth, dead branches later strapped around their trunks “like a tepee,” then set on fire and burned to the ground. The work was non-stop. At night, it is said, Dockery’s was a murky cauldron of fire and smoke. When Dockery’s land was finally cleared, it wasn’t always a smooth transition to farm work. As one man put it, “Times was so tough we couldn’t cut it with a knife, man. Plowing four mules … hitting them stumps and that plow kicking you all in the stomach.” It was difficult work for years and years.

Dockery was a no-nonsense kind of man, and his investment of time and labor in this seemingly unpropitious location proved almost immediately successful, coinciding as it did with an incredible surge in cotton prices. In the fifteen-year span beginning in 1898, cotton prices rocketed, rising 121 percent after a quarter century of stagnation, with annual production in the United States increasing from its pre-Civil War average of 5,386,000 bales to 13,500,000 by 1920. Importers in Britain and on the Continent, desperate to satisfy worldwide demand, despaired that there might not be a sufficient supply of raw material. They feared a “cotton famine,” much as they had after 1865 when the thought of freed Negroes fleeing the farm caused equal uncertainty. Dockery, in a business sense, was in the right place at the right time, and he moved aggressively to increase his holdings and to invest in infrastructure.

At his own expense he built a two-storey railroad depot to attract the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad, who were building a one-track narrow gauge line intended to connect far-flung plantations like his with both their main Memphis route and the river port of Rosedale. Before useable roads were built, trains were the only efficient way of getting lumber and raw cotton quickly to market, the era of steamboats slowly dying away. This little branch line came to be known as the Pea Vine, given its meandering route, sluggish pace, and multitude of flag stops where anyone waving a hankie could stop the train and climb on board. As the only practical way of getting anywhere, it stood as a metaphor for moving on, and became a mainstay of blues imagery. Charlie Patton’s “Pea Vine Blues” is typical (“I’m goin’ up the country, Mama, in a few more days”). David Cohn, a well-connected and affluent white born in Greenville, Mississippi, 1894 and the author of God Shakes Creation, wrote nostalgically of lines like the Pea Vine.

The bell of the locomotive clanged. The dinky train chugged past the sawmill, the whine of the saws in my ears as they ripped through the stout hearts of oak logs, the pungent sweetish aroma of green lumber in my nostrils, and in my mind the words of the haunting Negro song:

Ain’t but the one train on the track,

Gwing straight to heaven

An’ it ain’t coming back.

In this booming though isolated environment (no gravel roads until 1915, electricity unavailable until the late 1920s), Charlie Patton lived his youth. Again, details are sparse, but he clearly found his niche in the field of entertaining others, not so much as a plantation minstrel playing for the master (Will Dockery had no interest in music), but in something decidedly more lowlife. He played in the “slave quarters,” his audience consisted of illiterate field hands like himself in the combustible atmosphere of “house parties” and plantation “frolics” — Pops Staples called them “breakdowns” — “screaming and hollering” as he sang in one of his more popular tunes. In this insular world, he became something akin to a superstar.

Charlie

“What he can’t do with a guitar ain’t worth mentioning.”

Promotional blurb, Paramount Records, 1929

Charlie Patton was a slightly built string bean of a man. Unlike most blacks, he had a light complexion and smooth curly hair, which made some people think he was a half-breed. More likely he may have had Indian blood mixed in somewhere, from the Choctaw peoples who originally lived in the Delta. Others suspect some white element which, given the sexual crimes perpetuated against Afro-American women suggested by lore and word of mouth anecdote, is certainly possible (this stereotypically lurid notion is often ridiculed by Southern white intelligensia, one of whom noted the usual canard regarding plantation-style degeneracy: “Father is a slobbering drunkard; Mother, an ineffectual dreamer living in the past; Sister, an apprentice nymphomaniac; Junior a reckless youth having a love affair with a Negro girl (his father’s daughter and therefore his half-sister) in the bottoms below the white-columned house crumbling to ruins. In the attic live two crazy aunts. On the moonlight nights they dress themselves in the finery of their ancestors, steal out on the mangy lawn, and do a wild ballet.”[2]

During Patton’s prime, Dockery’s was running full steam ahead. Something like 400 families were spread about the plantation, some 2,000 people, usually sharecropping from ten to fifteen acres each. Their shotgun houses, hardly more than shacks, had no running water, no electricity, were stifling in the summer and often frigid in winter. Some had a rickety shed nearby, perhaps with a cow and pigs as tenants, plus a vegetable garden. Our outhouse, as one remembered, “was about twenty feet in back of the house at the edge of our watermelon patch. I mention this because the melons always seemed to be bigger.” Will Dockery’s son, Joe Rice, claimed that his family never bilked these men come settling time, usually a day or two before Christmas when each farmer squared his account with the boss man, and perhaps he’s being truthful. The Dockery family, whether through interviews they gave or as a the result of the positive spin that the current foundation which maintains the central complex churns out, has enjoyed a reputation of benevolent paternalism. The Dockerys were no tyrants, and the saying goes that an ambitious man “had a better chance of breaking even” there than at most plantations in the area, which can probably be filed under the heading of “faint praise.”[3]

Certainly on many plantations, exploitation remained the rule. A memoir written by John Oliver Hodges about growing up near Clarksdale in the 1950s repeated the familiar lament. “No matter how hard we worked, we always seemed to come out in the hole” and thus dependent on a cash advance to get going the next year, always a prescription for more debt. As he wrote, quoting an old rhymed saying,

Five’s a figger,

Always for the white man,

But none for the nigger.

On the plus side, however, by all accounts Will Dockery was not an ostentatious or vainglorious man. Though his family was native to Mississippi, and his father a Confederate colonel wounded in the war, he did not drag these connotations throughout his own life as some sort of emblematic totem. He refused to call himself a “planter,” or Dockery a “plantation.” Instead, his stationery carried the words “Merchant & Farmer,” a not very subtle rebuke to many of his neighbors, who considered themselves landed aristocracy. “Farmer” to many of them meant white trash working a few barren acres in the hilly uplands that border the Delta to the east and south. David Cohen, born in Greenville, wrote a chapter of memoirs recalling his childhood which emphasized this distinction, constantly reduced to the level of cliché in both the minds of many of his friends and in the pages of cheap fiction. The planter, he said, was never a farmer. “The planter occasionally died in a duel; the farmer of lockjaw got by stepping on a rusty nail.” Will Dockery loved the outdoors, tracking game, fishing, and riding, but he never dressed himself up in a hunt cap, scarlet jacket, white breeches and leather boots to chase foxes, as William Faulkner did.

A Will Dockery was desperate for men willing to work. Clearing his farm was a backbreaking and expensive venture. The portions of Dockery’s wilderness that were not under water when he first saw it were covered with cane bush and undergrowth that often stood over fifteen feet high. Land had to be drained, trees cut, stumps pulled out, and cotton seeds put to ground as quickly as possible. In his haste, many trees were left in situ, slashed of bark around their girth, dead branches later strapped around their trunks “like a tepee,” then set on fire and burned to the ground. The work was non-stop. At night, it is said, Dockery’s was a murky cauldron of fire and smoke. When Dockery’s land was finally cleared, it wasn’t always a smooth transition to farm work. As one man put it, “Times was so tough we couldn’t cut it with a knife, man. Plowing four mules … hitting them stumps and that plow kicking you all in the stomach.” It was difficult work for years and years.

Dockery was a no-nonsense kind of man, and his investment of time and labor in this seemingly unpropitious location proved almost immediately successful, coinciding as it did with an incredible surge in cotton prices. In the fifteen-year span beginning in 1898, cotton prices rocketed, rising 121 percent after a quarter century of stagnation, with annual production in the United States increasing from its pre-Civil War average of 5,386,000 bales to 13,500,000 by 1920. Importers in Britain and on the Continent, desperate to satisfy worldwide demand, despaired that there might not be a sufficient supply of raw material. They feared a “cotton famine,” much as they had after 1865 when the thought of freed Negroes fleeing the farm caused equal uncertainty. Dockery, in a business sense, was in the right place at the right time, and he moved aggressively to increase his holdings and to invest in infrastructure.

At his own expense he built a two-storey railroad depot to attract the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad, who were building a one-track narrow gauge line intended to connect far-flung plantations like his with both their main Memphis route and the river port of Rosedale. Before useable roads were built, trains were the only efficient way of getting lumber and raw cotton quickly to market, the era of steamboats slowly dying away. This little branch line came to be known as the Pea Vine, given its meandering route, sluggish pace, and multitude of flag stops where anyone waving a hankie could stop the train and climb on board. As the only practical way of getting anywhere, it stood as a metaphor for moving on, and became a mainstay of blues imagery. Charlie Patton’s “Pea Vine Blues” is typical (“I’m goin’ up the country, Mama, in a few more days”). David Cohn, a well-connected and affluent white born in Greenville, Mississippi, 1894 and the author of God Shakes Creation, wrote nostalgically of lines like the Pea Vine.

The bell of the locomotive clanged. The dinky train chugged past the sawmill, the whine of the saws in my ears as they ripped through the stout hearts of oak logs, the pungent sweetish aroma of green lumber in my nostrils, and in my mind the words of the haunting Negro song:

Ain’t but the one train on the track,

Gwing straight to heaven

An’ it ain’t coming back.

In this booming though isolated environment (no gravel roads until 1915, electricity unavailable until the late 1920s), Charlie Patton lived his youth. Again, details are sparse, but he clearly found his niche in the field of entertaining others, not so much as a plantation minstrel playing for the master (Will Dockery had no interest in music), but in something decidedly more lowlife. He played in the “slave quarters,” his audience consisted of illiterate field hands like himself in the combustible atmosphere of “house parties” and plantation “frolics” — Pops Staples called them “breakdowns” — “screaming and hollering” as he sang in one of his more popular tunes. In this insular world, he became something akin to a superstar.

Charlie

“What he can’t do with a guitar ain’t worth mentioning.”

Promotional blurb, Paramount Records, 1929

Charlie Patton was a slightly built string bean of a man. Unlike most blacks, he had a light complexion and smooth curly hair, which made some people think he was a half-breed. More likely he may have had Indian blood mixed in somewhere, from the Choctaw peoples who originally lived in the Delta. Others suspect some white element which, given the sexual crimes perpetuated against Afro-American women suggested by lore and word of mouth anecdote, is certainly possible (this stereotypically lurid notion is often ridiculed by Southern white intelligensia, one of whom noted the usual canard regarding plantation-style degeneracy: “Father is a slobbering drunkard; Mother, an ineffectual dreamer living in the past; Sister, an apprentice nymphomaniac; Junior a reckless youth having a love affair with a Negro girl (his father’s daughter and therefore his half-sister) in the bottoms below the white-columned house crumbling to ruins. In the attic live two crazy aunts. On the moonlight nights they dress themselves in the finery of their ancestors, steal out on the mangy lawn, and do a wild ballet.”[2]

During Patton’s prime, Dockery’s was running full steam ahead. Something like 400 families were spread about the plantation, some 2,000 people, usually sharecropping from ten to fifteen acres each. Their shotgun houses, hardly more than shacks, had no running water, no electricity, were stifling in the summer and often frigid in winter. Some had a rickety shed nearby, perhaps with a cow and pigs as tenants, plus a vegetable garden. Our outhouse, as one remembered, “was about twenty feet in back of the house at the edge of our watermelon patch. I mention this because the melons always seemed to be bigger.” Will Dockery’s son, Joe Rice, claimed that his family never bilked these men come settling time, usually a day or two before Christmas when each farmer squared his account with the boss man, and perhaps he’s being truthful. The Dockery family, whether through interviews they gave or as a the result of the positive spin that the current foundation which maintains the central complex churns out, has enjoyed a reputation of benevolent paternalism. The Dockerys were no tyrants, and the saying goes that an ambitious man “had a better chance of breaking even” there than at most plantations in the area, which can probably be filed under the heading of “faint praise.”[3]

Certainly on many plantations, exploitation remained the rule. A memoir written by John Oliver Hodges about growing up near Clarksdale in the 1950s repeated the familiar lament. “No matter how hard we worked, we always seemed to come out in the hole” and thus dependent on a cash advance to get going the next year, always a prescription for more debt. As he wrote, quoting an old rhymed saying,

Five’s a figger,

Always for the white man,

But none for the nigger.

On the plus side, however, by all accounts Will Dockery was not an ostentatious or vainglorious man. Though his family was native to Mississippi, and his father a Confederate colonel wounded in the war, he did not drag these connotations throughout his own life as some sort of emblematic totem. He refused to call himself a “planter,” or Dockery a “plantation.” Instead, his stationery carried the words “Merchant & Farmer,” a not very subtle rebuke to many of his neighbors, who considered themselves landed aristocracy. “Farmer” to many of them meant white trash working a few barren acres in the hilly uplands that border the Delta to the east and south. David Cohen, born in Greenville, wrote a chapter of memoirs recalling his childhood which emphasized this distinction, constantly reduced to the level of cliché in both the minds of many of his friends and in the pages of cheap fiction. The planter, he said, was never a farmer. “The planter occasionally died in a duel; the farmer of lockjaw got by stepping on a rusty nail.” Will Dockery loved the outdoors, tracking game, fishing, and riding, but he never dressed himself up in a hunt cap, scarlet jacket, white breeches and leather boots to chase foxes, as William Faulkner did.

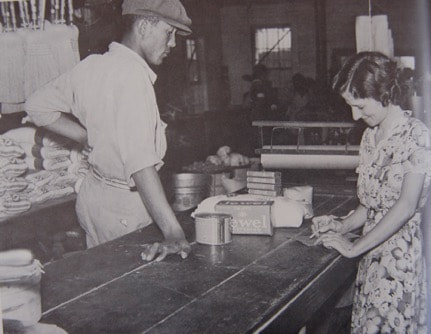

Settling up at a plantation office, 1939

Settling up at a plantation office, 1939

By 1900, it has been estimated that 30 percent of the swamp land between the Yazoo River and the Mississippi had been reclaimed. Dockery himself would have another decade of work ahead of him before turning the corner on his own place. Demand for masses of workers remained high, and word was out on that score. At Dockery’s, day laborers mostly lived in the twelve or so boarding houses that were set up on the other side of the Sunflower River, across from the cotton gin. These were run by older woman, for the most part, and accommodated bachelor men, often transient workers there for the season and perhaps no more. As with most plantations, men rose early and worked late. As one from a neighboring plantation said to an interviewer, “I had to git up around three in the morning by a bell. The bell rang two times. First time you git up. The second time, be at the barn. Not on your way, [but] at the barn.” Once chores were assigned or laborers sent to the fields either to plough or pick, they were supervised by managers called “riders” because they ran the place from the saddle, or “rode” men to work harder. When Saturday night came along, men were ready for just about anything. [4]

Charlie and his ilk often warmed up on the commissary porch, the plantation’s commercial hub. Dockery’s had seven clerks who sold everyday goods and supplies to the workers and their women who, practically speaking, had no other place to go for shopping and necessities. Cash was usually in short supply, so Dockery’s had its own currency, or “script.” Script was just another way to control plantation workers, though plantation owners, if they were pressed, would say it was just sound business practice. Some tenant farmers, when they received a cash advance on the next spring’s planting, were sometimes known to skip off with the money in their pockets. Script kept them committed to the plantation, since the tender was only occasionally accepted elsewhere. It likewise recycled monetary value within the boundaries of the estate. What men received as wages they often spent at the commissary, owned and operated by men like Dockery. On Saturdays, it was a busy place, and Charlie sang a few songs, with promises for more when the sun went down. He was, essentially, advertising his services and telling people where he’d be.

Saturday night was “nigger night,” the time of the week when blacks pretty much owned the place. Men from the outskirts of Dockery’s would start walking in early to get there in good time, or hitch up their mules to the wagon and come on in. They’d lounge around in the afternoon, shooting the breeze, until the action started. As Joe Rice Dockery put it, “the blues was a Saturday night deal. The crap games would start about noon Saturday, and then the niggers would start getting drunk. I’ve seen niggers stumbling all over this place on a Saturday afternoon. And then they’d have a frettin’ and fightin’ scrapes that night … there were killings, but really very few, and it was nothing premeditated. People would be drinking, and there’d be a spontaneous argument between men in the group. Women played a big part in that. You know the best thing B.B. King [once] said is that the blues means when a man has lost his woman. Which was all he had. He didn’t have anything else.” According to the music critic Robert Palmer, who interviewed Dockery in 1979, some of these “frolics” drew huge crowds, with hundreds of people milling around, many from other plantations. William Faulkner has a character in The Reivers who put his thumb on it. “You’re the wrong color. If you could just be a nigger one Saturday night, you wouldn’t never want to be a white man again as long as you live.” In this world, Charlie Patton was a big draw.

Charlie and his ilk often warmed up on the commissary porch, the plantation’s commercial hub. Dockery’s had seven clerks who sold everyday goods and supplies to the workers and their women who, practically speaking, had no other place to go for shopping and necessities. Cash was usually in short supply, so Dockery’s had its own currency, or “script.” Script was just another way to control plantation workers, though plantation owners, if they were pressed, would say it was just sound business practice. Some tenant farmers, when they received a cash advance on the next spring’s planting, were sometimes known to skip off with the money in their pockets. Script kept them committed to the plantation, since the tender was only occasionally accepted elsewhere. It likewise recycled monetary value within the boundaries of the estate. What men received as wages they often spent at the commissary, owned and operated by men like Dockery. On Saturdays, it was a busy place, and Charlie sang a few songs, with promises for more when the sun went down. He was, essentially, advertising his services and telling people where he’d be.

Saturday night was “nigger night,” the time of the week when blacks pretty much owned the place. Men from the outskirts of Dockery’s would start walking in early to get there in good time, or hitch up their mules to the wagon and come on in. They’d lounge around in the afternoon, shooting the breeze, until the action started. As Joe Rice Dockery put it, “the blues was a Saturday night deal. The crap games would start about noon Saturday, and then the niggers would start getting drunk. I’ve seen niggers stumbling all over this place on a Saturday afternoon. And then they’d have a frettin’ and fightin’ scrapes that night … there were killings, but really very few, and it was nothing premeditated. People would be drinking, and there’d be a spontaneous argument between men in the group. Women played a big part in that. You know the best thing B.B. King [once] said is that the blues means when a man has lost his woman. Which was all he had. He didn’t have anything else.” According to the music critic Robert Palmer, who interviewed Dockery in 1979, some of these “frolics” drew huge crowds, with hundreds of people milling around, many from other plantations. William Faulkner has a character in The Reivers who put his thumb on it. “You’re the wrong color. If you could just be a nigger one Saturday night, you wouldn’t never want to be a white man again as long as you live.” In this world, Charlie Patton was a big draw.

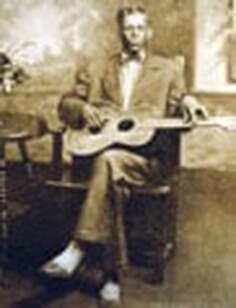

The only known photograph of Charlie Patton

The only known photograph of Charlie Patton

A white man’s attitude to such goings-on was often contradictory and morally confusing. Joe Rice Dockery, for all we know, was a righteous family man who would never have given a thought to rolling around on his front lawn drunk as a skunk, or pulling a knife in some lowlife craps game. He had a wife and daughter, he would not have wanted to humiliate them in such fashion. On the other hand, could he in some wistful way have been jealous of a roustabout life with no restraints? The research done by sociologists in the 1930s, when teams of academics did indeed “study” southern life, were often riddled with paradoxical musings. One plantation owner, when asked about it, said, “I often think the Negroes are happier than whites no matter how little they have. You always see them smiling and happy as long as they have a little to eat. One reason they’re so carefree is that they have no morals to worry about and they don’t have to keep up their good name.”

Usually farmhands knew a party spot beforehand, but if they didn’t, venues for a frolic would have a mirror out on the porch with lanterns in front to project illumination. There might be a small entry fee, there’d be craps in the back, some BBQ to purchase, plenty of moonshine, and Charlie playing in the front room, cleared for dancing. And one thing about Charlie Patton, “he didn’t need no mic.”

According to Son House, who played with Patton toward the end of Charlie’s life, “them country balls were rough …They’d start off good, you know. Everyone happy, dancing, and then they’d start getting louder and louder. The women would be dipping that snuff and swallowing that snuff spit along with that corn whiskey, and they’d start to mixing fast, and oh brother! They’d start something then.” Charlie’s style of play whipped up the energy, which is only partially apparent from his recordings. In the studio, he (and all the other blues artists who made it that far) was regulated to about three minutes per song, the physical limits of the discs. But “in concert,” as it were, a single song might last twenty minutes or longer, building up to a frenzied climax. Charlie “could whoop and holler and sing … that’s what made him known. He beat everybody hollering.” He kept the percussion going too, usually stomping his feet on the floor (some players had steel clips on their shoe heels for heightened effect) or thumping his “box,” as a guitar was known. (“This is the way I beat my woman,” he’d say, and the crowd would love it, at least until the fists started flying). Just listen to “High Water Everywhere, Part I,” for what would be a typical dance tune. Lyrics were often improvised and, depending on how much Charlie was drinking, sometimes incoherent, especially as a tune dragged on, but his vocal cords could handle it. “He had a voice,” one old-timer remembered, “he had a voice!” Son House, interviewed after his own “rediscovery” in the 1960s, took a more jaundiced view of his old buddy. His songs “would sound alright,” he recalled. “Some of them had a meaning to them, some didn’t. That’s the way he played: he’d just say anything he could think of, ‘Hey baby,’ [and go from there].” Another contemporary noted that “the blues is kinda like workin’ in a church, I guess. Whatever the ‘spirit’ say do, you do it.”

As a way of keeping everyone involved, Patton would haul out his bag of tricks as well, being a consummate showman. He could pick his guitar from behind his head, throw it up in the air and catch it, twirl it around on the floor, ride it like a pony, anything to work people up. He could also keep going. “He could endure, you know what I mean?” said Booker “Mr. Pink” Miller. “He didn’t get tired and lay his box down and walk out like so many musicians would do, standing around talkin’ about, ‘I’m tired.’ If it took all night he'd be there with you. If you said, ‘Start at seven o’clock,’ he’d be right there. And you say, ‘We goin’ till daylight,’ he’d be right there. You never would hear nobody comin’ in and saying, “Wonder where he at? What’s the matter with the music?’ Cause it would be going. I never saw him get too drunk to play; he’s play anyhow. I don’t know how, but he could do it … keep [swinging] .... He just put so much into it.” Patton’s hijinks, and penchant for flirting, would ratchet up as the night wore on, but with often perilous effect.

Three things Charlie could do: he could play the guitar, drink, and chase women. As far as playing guitar, he was a master; as far as holding his liquor, decidedly less so; as for women, he had his ups and downs, mostly downs.

No can deny that Patton had a drinking problem. As he grew older, he generally preferred, and sometimes could afford, decent stuff, “Bottle n’ Bond,” 100 proof, aged whiskey that was usually warehoused for a year under government supervision; barring that, illegal corn whiskey, moonshine stuff but potent; barring that, whatever gave a kick (sterno comes to mind).[5] Despite Miller’s protestations noted above, Charlie had the reputation of getting blind drunk as the night wore on, which aggravated his penchant for getting “meddlesome.” “He’d call anybody’s wife ‘honey’ and ‘sugar,’” said Willie “Have Mercy” Young, and “a real jealous man didn’t have no business around Charlie Patton.” Another crony recalled that “when he “started talking them blues, the women’d start to popping their fingers and skippin’, and then them niggers [i.e. their men] turn and say, ‘Let’s get away from here.’” Charlie’s matrimonial history reflected his popularity with the opposite sex: his wives (legal or otherwise), live-in girlfriends, and various amorous liaisons were too numerous to keep track of. Some of those we find mentioned, often at varying moments in Charlie’s wanderings, are Gertrude, Lizzie, Roxie, Mandy, Dela, Minnie, Millie, Roxie, Udy, Polly, Bessie, Katie, Bertha Lee, Louise, and Willie. There were surely more. As he sang in “Pony Blues,”

Don’t want to marry

Just want to be your man

Or, perhaps being more sarcastic, there’s a song Willie Brown recorded in 1941 called “Make Me a Pallet on the Floor,”

Now, I love you babes, ‘cause you so nice an’ brown

‘Cause you tailor-made an’ you ain’ no hand-me-down.[6]

“He thought he was some pig meat back in those days,” Son House told an interviewer. “Charlie’d meddle all the time, and then get a big laugh off it.” Son House, especially later in his life, considered himself a blues purist. Charlie’s clowning around and show biz antics, meant to lure women into his honey trap, annoyed him no end. Patton was a “jerk” and a “shit ass.” He also paid for his indiscretions. There is some credence to the rumor that Charlie was shot by a disgruntled husband or boyfriend at one point after a frolic, though no solid proof exists, other than that he started limping. What is undeniable is that his throat was slashed with a razor in 1929, an incident he was lucky to survive. In the only known photograph of Patton, his shirt collar and bow tie are slightly hiked by his left-hand shoulder; it has been suggested by several writers that this was purposely done to disguise the scar.

All this suggests the kind of socio-economic milieu in which Charlie Patton both lived his life and, to some degree, thrived. It is not a particularly genteel or refined world, which is saying the obvious, but it was the milieu of the blues. Afro-Americans living near towns or working along the banks of the Mississippi, or loading and offloading cargoes on the wharves of bigger cities like Memphis, had a variety of black musical entertainment to sample: marching brass bands, minstrel shows at vaudeville theatres, ragtime in bars or brothels, sacred music on Sundays. Plantation workers at Dockery’s pretty much had church music and that was it, except for the Saturday night bluesmen. Out of the mainstream as it was, the bluesman could thrive at a place like Dockery’s, as he could on any number of other plantations and low-down dives along the Mississippi, in places like Natchez, Rosedale, and Vicksburg. This was the lowest denominator, in contemporary opinion, on the musical ladder. These guys were the “skid row” of the musical fraternity.

Despite all this, what made him great?

We’re back to asking the same question here that we asked about Robert Johnson earlier. What made Charlie great? To answer that, we should first, I think, get past the showmanship angle. We know he was popular, we know he could hold people’s attention, we know he had exhibitionist tendencies that later stars like a Chuck Berry, an Elvis Presley, and a Jimmy Hendrix would emulate, however little they knew about Patton other than generalities. Playing a guitar behind your neck or gyrating like a madman aren’t exactly patented moves “invented” by anyone. In the noisy, rowdy, and manic atmosphere of house frolics, you needed to command the stage or be hooted off it, and Charlie fought hard to keep the metaphorical spotlight on himself, very difficult indeed when your audience was fired up (“racket’s all they want,” said one musician regarding frolics). When people, especially overwrought women, interfered with the show or moved in to grab center stage themselves, Patton reacted, being, as a contemporary called him, “kind of fractious.” There are anecdotal stories about Charlie hitting people over the head with his guitar when the action veered out of his control. So we know he was a showman, we know he was charismatic in his own way; but how about his musicianship? How was he special?

If blues guitar style is known for anything, it’s the slide, often a bottleneck whose rough edges have been smoothed away, or a short piece of copper tubing slipped on a finger of the left hand (some players used the dull edge of a knife as their slide). A skilled guitarist can extend the expressiveness, range, and pitch of the guitar like a human voice when it keens or “howls” by dragging the slide along the frets, usually to a higher note, and stretching it out, as it were. The most apt comparison would be the trombone, with its elongated “slide,” vis-à-vis (let’s say) the trumpet. A trumpet hits a certain note, but a trombone can range about the scale at will.

In technique, Patton was a guitar player of remarkable fluidity who had a great rhythmic sense, the capability to play multiple “storylines” at once (bass and lead), using four fingers on his right hand to pick notes, and his thumb to establish the bass chords (in different measures), with percussion (slapping the guitar or stomping his feet) to underlie the whole song. Patton’s mastery of the slide was phenomenal, almost an extra voice that extended the emotional range of a particular song. A master like Charlie didn’t need the frets on his guitar, because the slide, when pulled along the strings (“worrying” them, as musicians put it), ignored “notes” per se and became something of a whine or “extender.” Slide added expression and vibrato to whatever he was singing, the stretching of emotion, usually something bleak or sad. It can be the moment in the song – let’s say it’s David Gilmore of Pink Floyd hitting a high note – when you’d expect to see the guitarist wince or jerk his head up or “climax” the riff in some such bodily reaction.

Slide techniques enriched the song, emphasized its message (however simplistic) and made the mood bluer than blue. The slide has some precedence in the history of music -- when W. C. Handy first heard it used at the Tutwiler train station, he was reminded of Hawaiian music -– but early bluesmen were really trailblazers in its application and development. If you want to hear a modern usage, listen to Brian Jones on “Little Red Rooster,” a Rolling Stones hit from 1964 (a cover of a Willie Dixon tune, and the first recording to reach Number 1 on the UK charts with a guitar player using the slide).

To the casual listener of Patton’s tunes, these attributes may seem too grandiose, given the simplicity of the 12-bar blues form. That is a tribute to Charlie’s technical talents, because his skills were often very subtle and easily lost to those of us who are not professional musicians. His melodies were not particularly varied, but within his core repertoire he displayed great virtuosity and an abundance of what one critic called “varieties of expression.” He could play it fast, play it slow, with many twists in between. The accomplished blues harmonica player Charlie Musselwhite said it best: “Sounds simple, but you try to play it.”

Musicianship aside, Patton also had an enormously distinctive voice, not silky in the fashion of a Robert Johnson, but more like a cement mixer just after sand and gravel have been added to the slosh. Technically a baritone, Patton could change his tone, range, and inflection at will. Frequently, in listening to his often indecipherable lyrics, a second seemingly different voice chimes in with an encouraging push, something like a “My God, I’m gonna sing’em” or “Babe, you know I can’t stay,’” which was usually Patton himself. His vocal range, not that broad, was unusually dense and totally distinctive. At a “blind tasting,” as it were, if someone played a Charlie Patton song and asked you, who’s singing that, anyone who knows anything would recognize his voice in a second. I’m reminded here of what Ronnie Hawkins said when he heard Howlin’ Wolf sing: he “had a hell of a voice,” he remarked, “it was stronger than forty acres of crushed garlic.” I get his point.

On top of all this, Patton was a true poet of feelings. I think he would have laughed in your face if anyone had described him in that way within earshot, but he had a descriptive ability to communicate what he, and his ilk down on the plantation, had on their minds (and not just sex). His lyrics, when you are able to decipher what they are, are often beautifully expressed, and blues at its best, and his influence on a legion of fine players and singers is indisputable (Tommy Johnson, Son House, Robert Johnson, Bukka White, Howlin’ Wolf, and Muddy Waters, among others).

The “Birthplace” of the Blues?

Sunflower County might as well have been a private, medieval kingdom, so remote and isolated was it from anything mainstream in American life –“within America,” as David Cohn put it,” and yet withdrawn from it.” There were few if any roads, none paved. When H. C. Speir drove up from Jackson to audition Charlie Patton in 1929, it took him half a day to travel 100 miles. County barons, like Will Dockery, lorded over an entirely subservient working class of mostly illiterate field hands, dominating just about every facet of their lives. He rented them their farms and shacks, furnished them (on credit) with seeds, supplies, mules, carts, and equipment, sold them food in their company stores, and often liquor and women in plantation brothels. In terms of law and order, the plantation owner dispensed both. Mississippi, like adjoining southern states, was politically dominated by its landowning class, and legislation involving security was written with their interests mostly in mind. Many sheriffs in local communities had little or no jurisdiction when it came to plantation issues, other than the grossest of offenses such as murder, and even then, if the killer was a good worker, sheriffs could be argued out of making an arrest. Revenue agents, as another example, were not allowed to ferret out illegal stills on Dockery Farms, the allowance for which most plantation owners winked an eye at, however unwillingly. Some, more enlightened than others, had a doctor on hand to cope with injuries, and cooperated with health officials when they came around to deal with local scourges such as malaria. Will Dockery paid half the bill for quinine brought down to the plantation by social workers hired by the Rockefeller Foundation. Relatively healthy laborers were far better for the bottom line than dead ones.

Which leads to the basic dichotomy of trying to control large numbers of laborers, first during the slavery years, then afterwards when they were nominally “free.” Coercion was always at the root of slavery. Anyone attempting to flee, or trying to revolt was routinely punished in the most savage manner. Beatings, torture, overseers carrying bullwhips, right on through to lynching. On the other hand, without slaves, or without “indentured” laborers, “white gold,” as cotton was called, could not be planted, tended, or harvested. Until mechanization revolutionized the industry in the mid twentieth century, cotton remained the most labor-intensive crop in the United States. No labor force meant no cotton. While cotton prices often fluctuated, and demands for labor with it, the basic dependence was never questioned. The Afro-America worker was the single most important element in the business, but also the most denigrated, abused, and exploited. As cotton empires thrived and grew, particularly in the Delta, the growing interdependence with European markets, and particularly with Britain, grew along with it. British banks and money houses played a vital role in capitalizing expansion and innovation throughout the South, and what was the primary commodity that was initially used as collateral in most loans? Slaves. In Louisiana alone, something like 88 per cent of all mortgages were backed by actual slaves. If the loan failed, or the borrower went bankrupt, the holder of his note was entitled to the possession of specific slaves. Their value, according to some historians, represented “hundreds of millions of dollars in capital,” just another odiferous aspect of the business. Would a more benevolent system have produced more profit and more business from Britain, with a correspondingly less corrosive moral tincture? Perhaps, but human nature being what it is, the urge to dominate, control, and play the king cannot be trumped, in most instances, by the attractions of more restrained and worthy behavior. Will Dockery, for instance, was not an evil man, but he was, unquestionably, the boss.

Usually farmhands knew a party spot beforehand, but if they didn’t, venues for a frolic would have a mirror out on the porch with lanterns in front to project illumination. There might be a small entry fee, there’d be craps in the back, some BBQ to purchase, plenty of moonshine, and Charlie playing in the front room, cleared for dancing. And one thing about Charlie Patton, “he didn’t need no mic.”

According to Son House, who played with Patton toward the end of Charlie’s life, “them country balls were rough …They’d start off good, you know. Everyone happy, dancing, and then they’d start getting louder and louder. The women would be dipping that snuff and swallowing that snuff spit along with that corn whiskey, and they’d start to mixing fast, and oh brother! They’d start something then.” Charlie’s style of play whipped up the energy, which is only partially apparent from his recordings. In the studio, he (and all the other blues artists who made it that far) was regulated to about three minutes per song, the physical limits of the discs. But “in concert,” as it were, a single song might last twenty minutes or longer, building up to a frenzied climax. Charlie “could whoop and holler and sing … that’s what made him known. He beat everybody hollering.” He kept the percussion going too, usually stomping his feet on the floor (some players had steel clips on their shoe heels for heightened effect) or thumping his “box,” as a guitar was known. (“This is the way I beat my woman,” he’d say, and the crowd would love it, at least until the fists started flying). Just listen to “High Water Everywhere, Part I,” for what would be a typical dance tune. Lyrics were often improvised and, depending on how much Charlie was drinking, sometimes incoherent, especially as a tune dragged on, but his vocal cords could handle it. “He had a voice,” one old-timer remembered, “he had a voice!” Son House, interviewed after his own “rediscovery” in the 1960s, took a more jaundiced view of his old buddy. His songs “would sound alright,” he recalled. “Some of them had a meaning to them, some didn’t. That’s the way he played: he’d just say anything he could think of, ‘Hey baby,’ [and go from there].” Another contemporary noted that “the blues is kinda like workin’ in a church, I guess. Whatever the ‘spirit’ say do, you do it.”

As a way of keeping everyone involved, Patton would haul out his bag of tricks as well, being a consummate showman. He could pick his guitar from behind his head, throw it up in the air and catch it, twirl it around on the floor, ride it like a pony, anything to work people up. He could also keep going. “He could endure, you know what I mean?” said Booker “Mr. Pink” Miller. “He didn’t get tired and lay his box down and walk out like so many musicians would do, standing around talkin’ about, ‘I’m tired.’ If it took all night he'd be there with you. If you said, ‘Start at seven o’clock,’ he’d be right there. And you say, ‘We goin’ till daylight,’ he’d be right there. You never would hear nobody comin’ in and saying, “Wonder where he at? What’s the matter with the music?’ Cause it would be going. I never saw him get too drunk to play; he’s play anyhow. I don’t know how, but he could do it … keep [swinging] .... He just put so much into it.” Patton’s hijinks, and penchant for flirting, would ratchet up as the night wore on, but with often perilous effect.

Three things Charlie could do: he could play the guitar, drink, and chase women. As far as playing guitar, he was a master; as far as holding his liquor, decidedly less so; as for women, he had his ups and downs, mostly downs.

No can deny that Patton had a drinking problem. As he grew older, he generally preferred, and sometimes could afford, decent stuff, “Bottle n’ Bond,” 100 proof, aged whiskey that was usually warehoused for a year under government supervision; barring that, illegal corn whiskey, moonshine stuff but potent; barring that, whatever gave a kick (sterno comes to mind).[5] Despite Miller’s protestations noted above, Charlie had the reputation of getting blind drunk as the night wore on, which aggravated his penchant for getting “meddlesome.” “He’d call anybody’s wife ‘honey’ and ‘sugar,’” said Willie “Have Mercy” Young, and “a real jealous man didn’t have no business around Charlie Patton.” Another crony recalled that “when he “started talking them blues, the women’d start to popping their fingers and skippin’, and then them niggers [i.e. their men] turn and say, ‘Let’s get away from here.’” Charlie’s matrimonial history reflected his popularity with the opposite sex: his wives (legal or otherwise), live-in girlfriends, and various amorous liaisons were too numerous to keep track of. Some of those we find mentioned, often at varying moments in Charlie’s wanderings, are Gertrude, Lizzie, Roxie, Mandy, Dela, Minnie, Millie, Roxie, Udy, Polly, Bessie, Katie, Bertha Lee, Louise, and Willie. There were surely more. As he sang in “Pony Blues,”

Don’t want to marry

Just want to be your man

Or, perhaps being more sarcastic, there’s a song Willie Brown recorded in 1941 called “Make Me a Pallet on the Floor,”

Now, I love you babes, ‘cause you so nice an’ brown

‘Cause you tailor-made an’ you ain’ no hand-me-down.[6]

“He thought he was some pig meat back in those days,” Son House told an interviewer. “Charlie’d meddle all the time, and then get a big laugh off it.” Son House, especially later in his life, considered himself a blues purist. Charlie’s clowning around and show biz antics, meant to lure women into his honey trap, annoyed him no end. Patton was a “jerk” and a “shit ass.” He also paid for his indiscretions. There is some credence to the rumor that Charlie was shot by a disgruntled husband or boyfriend at one point after a frolic, though no solid proof exists, other than that he started limping. What is undeniable is that his throat was slashed with a razor in 1929, an incident he was lucky to survive. In the only known photograph of Patton, his shirt collar and bow tie are slightly hiked by his left-hand shoulder; it has been suggested by several writers that this was purposely done to disguise the scar.

All this suggests the kind of socio-economic milieu in which Charlie Patton both lived his life and, to some degree, thrived. It is not a particularly genteel or refined world, which is saying the obvious, but it was the milieu of the blues. Afro-Americans living near towns or working along the banks of the Mississippi, or loading and offloading cargoes on the wharves of bigger cities like Memphis, had a variety of black musical entertainment to sample: marching brass bands, minstrel shows at vaudeville theatres, ragtime in bars or brothels, sacred music on Sundays. Plantation workers at Dockery’s pretty much had church music and that was it, except for the Saturday night bluesmen. Out of the mainstream as it was, the bluesman could thrive at a place like Dockery’s, as he could on any number of other plantations and low-down dives along the Mississippi, in places like Natchez, Rosedale, and Vicksburg. This was the lowest denominator, in contemporary opinion, on the musical ladder. These guys were the “skid row” of the musical fraternity.

Despite all this, what made him great?

We’re back to asking the same question here that we asked about Robert Johnson earlier. What made Charlie great? To answer that, we should first, I think, get past the showmanship angle. We know he was popular, we know he could hold people’s attention, we know he had exhibitionist tendencies that later stars like a Chuck Berry, an Elvis Presley, and a Jimmy Hendrix would emulate, however little they knew about Patton other than generalities. Playing a guitar behind your neck or gyrating like a madman aren’t exactly patented moves “invented” by anyone. In the noisy, rowdy, and manic atmosphere of house frolics, you needed to command the stage or be hooted off it, and Charlie fought hard to keep the metaphorical spotlight on himself, very difficult indeed when your audience was fired up (“racket’s all they want,” said one musician regarding frolics). When people, especially overwrought women, interfered with the show or moved in to grab center stage themselves, Patton reacted, being, as a contemporary called him, “kind of fractious.” There are anecdotal stories about Charlie hitting people over the head with his guitar when the action veered out of his control. So we know he was a showman, we know he was charismatic in his own way; but how about his musicianship? How was he special?

If blues guitar style is known for anything, it’s the slide, often a bottleneck whose rough edges have been smoothed away, or a short piece of copper tubing slipped on a finger of the left hand (some players used the dull edge of a knife as their slide). A skilled guitarist can extend the expressiveness, range, and pitch of the guitar like a human voice when it keens or “howls” by dragging the slide along the frets, usually to a higher note, and stretching it out, as it were. The most apt comparison would be the trombone, with its elongated “slide,” vis-à-vis (let’s say) the trumpet. A trumpet hits a certain note, but a trombone can range about the scale at will.

In technique, Patton was a guitar player of remarkable fluidity who had a great rhythmic sense, the capability to play multiple “storylines” at once (bass and lead), using four fingers on his right hand to pick notes, and his thumb to establish the bass chords (in different measures), with percussion (slapping the guitar or stomping his feet) to underlie the whole song. Patton’s mastery of the slide was phenomenal, almost an extra voice that extended the emotional range of a particular song. A master like Charlie didn’t need the frets on his guitar, because the slide, when pulled along the strings (“worrying” them, as musicians put it), ignored “notes” per se and became something of a whine or “extender.” Slide added expression and vibrato to whatever he was singing, the stretching of emotion, usually something bleak or sad. It can be the moment in the song – let’s say it’s David Gilmore of Pink Floyd hitting a high note – when you’d expect to see the guitarist wince or jerk his head up or “climax” the riff in some such bodily reaction.

Slide techniques enriched the song, emphasized its message (however simplistic) and made the mood bluer than blue. The slide has some precedence in the history of music -- when W. C. Handy first heard it used at the Tutwiler train station, he was reminded of Hawaiian music -– but early bluesmen were really trailblazers in its application and development. If you want to hear a modern usage, listen to Brian Jones on “Little Red Rooster,” a Rolling Stones hit from 1964 (a cover of a Willie Dixon tune, and the first recording to reach Number 1 on the UK charts with a guitar player using the slide).

To the casual listener of Patton’s tunes, these attributes may seem too grandiose, given the simplicity of the 12-bar blues form. That is a tribute to Charlie’s technical talents, because his skills were often very subtle and easily lost to those of us who are not professional musicians. His melodies were not particularly varied, but within his core repertoire he displayed great virtuosity and an abundance of what one critic called “varieties of expression.” He could play it fast, play it slow, with many twists in between. The accomplished blues harmonica player Charlie Musselwhite said it best: “Sounds simple, but you try to play it.”

Musicianship aside, Patton also had an enormously distinctive voice, not silky in the fashion of a Robert Johnson, but more like a cement mixer just after sand and gravel have been added to the slosh. Technically a baritone, Patton could change his tone, range, and inflection at will. Frequently, in listening to his often indecipherable lyrics, a second seemingly different voice chimes in with an encouraging push, something like a “My God, I’m gonna sing’em” or “Babe, you know I can’t stay,’” which was usually Patton himself. His vocal range, not that broad, was unusually dense and totally distinctive. At a “blind tasting,” as it were, if someone played a Charlie Patton song and asked you, who’s singing that, anyone who knows anything would recognize his voice in a second. I’m reminded here of what Ronnie Hawkins said when he heard Howlin’ Wolf sing: he “had a hell of a voice,” he remarked, “it was stronger than forty acres of crushed garlic.” I get his point.

On top of all this, Patton was a true poet of feelings. I think he would have laughed in your face if anyone had described him in that way within earshot, but he had a descriptive ability to communicate what he, and his ilk down on the plantation, had on their minds (and not just sex). His lyrics, when you are able to decipher what they are, are often beautifully expressed, and blues at its best, and his influence on a legion of fine players and singers is indisputable (Tommy Johnson, Son House, Robert Johnson, Bukka White, Howlin’ Wolf, and Muddy Waters, among others).

The “Birthplace” of the Blues?

Sunflower County might as well have been a private, medieval kingdom, so remote and isolated was it from anything mainstream in American life –“within America,” as David Cohn put it,” and yet withdrawn from it.” There were few if any roads, none paved. When H. C. Speir drove up from Jackson to audition Charlie Patton in 1929, it took him half a day to travel 100 miles. County barons, like Will Dockery, lorded over an entirely subservient working class of mostly illiterate field hands, dominating just about every facet of their lives. He rented them their farms and shacks, furnished them (on credit) with seeds, supplies, mules, carts, and equipment, sold them food in their company stores, and often liquor and women in plantation brothels. In terms of law and order, the plantation owner dispensed both. Mississippi, like adjoining southern states, was politically dominated by its landowning class, and legislation involving security was written with their interests mostly in mind. Many sheriffs in local communities had little or no jurisdiction when it came to plantation issues, other than the grossest of offenses such as murder, and even then, if the killer was a good worker, sheriffs could be argued out of making an arrest. Revenue agents, as another example, were not allowed to ferret out illegal stills on Dockery Farms, the allowance for which most plantation owners winked an eye at, however unwillingly. Some, more enlightened than others, had a doctor on hand to cope with injuries, and cooperated with health officials when they came around to deal with local scourges such as malaria. Will Dockery paid half the bill for quinine brought down to the plantation by social workers hired by the Rockefeller Foundation. Relatively healthy laborers were far better for the bottom line than dead ones.

Which leads to the basic dichotomy of trying to control large numbers of laborers, first during the slavery years, then afterwards when they were nominally “free.” Coercion was always at the root of slavery. Anyone attempting to flee, or trying to revolt was routinely punished in the most savage manner. Beatings, torture, overseers carrying bullwhips, right on through to lynching. On the other hand, without slaves, or without “indentured” laborers, “white gold,” as cotton was called, could not be planted, tended, or harvested. Until mechanization revolutionized the industry in the mid twentieth century, cotton remained the most labor-intensive crop in the United States. No labor force meant no cotton. While cotton prices often fluctuated, and demands for labor with it, the basic dependence was never questioned. The Afro-America worker was the single most important element in the business, but also the most denigrated, abused, and exploited. As cotton empires thrived and grew, particularly in the Delta, the growing interdependence with European markets, and particularly with Britain, grew along with it. British banks and money houses played a vital role in capitalizing expansion and innovation throughout the South, and what was the primary commodity that was initially used as collateral in most loans? Slaves. In Louisiana alone, something like 88 per cent of all mortgages were backed by actual slaves. If the loan failed, or the borrower went bankrupt, the holder of his note was entitled to the possession of specific slaves. Their value, according to some historians, represented “hundreds of millions of dollars in capital,” just another odiferous aspect of the business. Would a more benevolent system have produced more profit and more business from Britain, with a correspondingly less corrosive moral tincture? Perhaps, but human nature being what it is, the urge to dominate, control, and play the king cannot be trumped, in most instances, by the attractions of more restrained and worthy behavior. Will Dockery, for instance, was not an evil man, but he was, unquestionably, the boss.

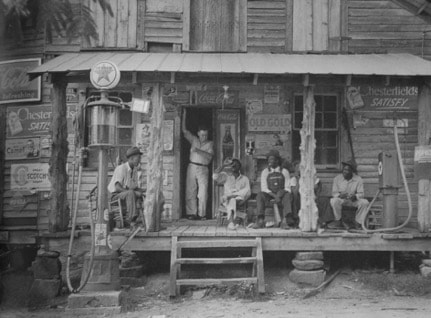

Another day older, and deeper in debt. A commissary store, 1939

Another day older, and deeper in debt. A commissary store, 1939

At the turn of the century, for example, farm owners like Dockery did not so much negotiate contractual issues with their tenant farmers as dictate them. Since most tenants had nothing in the way of property or possessions – one said that the average Negro laborer who showed up to work with his family at the beginning of planting season seldom had goods or clothing on them worth more than $30 – they stood disadvantaged from the beginning in trying to bargain for terms. “Negotiation was a white person’s prerogative,” as one historian pointed out.

People can argue all they want about where the blues came from, of where its “birthplace” was, or who should be granted the honorific title “father” of the blues. W. C. Handy, as we have noted, has often been singled out for that sort of recognition if only because he was one of first people to jot down on a piece of paper, in 1903, the profound impression that hearing an old blues song had made on him.

One indisputable fact, which I hope this book will make clear, is that the blues as we know them developed first here in the Delta and nowhere else. The relationship between blues and the historical, political, and geographical uniqueness of this several thousand acre, formerly obscure part of the country, are so intertwined as to make them inseparable. There had been slaves in America well before the blues were born, yet the blues did not develop in Virginia or South Carolina. Afro-Americans had ploughed behind mule packs before; they had performed pick and shovel work under dreadful conditions for generations; they had been abused, beaten, and lynched well before Reconstruction. Yet in those time spheres there were no blues songs in existence, and no performers singing them. So why did this whole artistic expression take shape in the Delta?