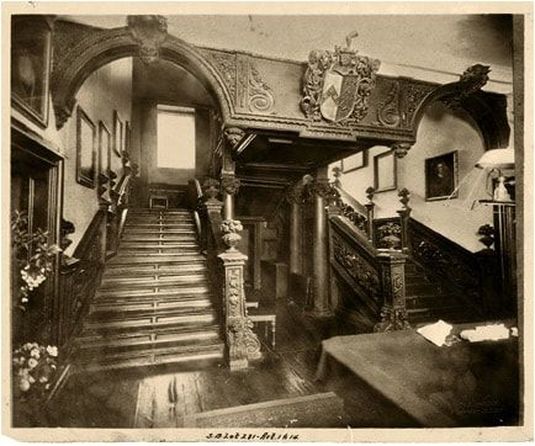

View of the staircase from the foyer entryway. Note the Eyre coat of arms

View of the staircase from the foyer entryway. Note the Eyre coat of arms

A shortened version of this article appeared in “The Journal of the Galway Archaeological & Historical Society,” Vol. 69 (2016), pp. 161-190.

William Randolph Hearst & The Eyrecourt Staircase

By James Charles Roy

Roughly ten miles south from the obscure East Galway town of Eyrecourt, off the Portumna Road, stand the well preserved remains of Derryhivenny Castle, constructed by one Daniel O’Madden in 1643, as a date chiseled into one of its remaining corbel stones tells us. Derryhivenny is not, in reality, a castle, but a fortified tower house, the likes of which form one of the most common relics of the Tudor and early Stuart eras in Ireland, representing as it does the unsettled times through which a man like O’Madden had to navigate. A landowner of considerable local stature, he sought from his home what others of his rank shared in common, a measure of protection from the turbulence that lay just outside his gated walls, as opposed to comfort.[1] A bare twenty years later, however, the Protestant Colonel John Eyre, a Cromwellian officer feasting on the spoils of military triumph, constructed his own “castle,” which he grandly christened Eyrecourt Castle. Despite the sometimes tenuous hold that English forces exercised over the countryside, and especially those lands west of the Shannon, Eyre evidently held a sanguine eye for the future. He constructed for himself and family (on lands once dominated by the aforementioned O’Maddens) a house built for pleasure. Instead of a high stone tower with narrow embrasures which barely passed as windows, and castellated ramparts from which inhabitants under siege could throw or shoot projectiles on enemies below, Eyrecourt Castle was a three-storey mansion without any pretense of a military function. Light, airy, grand rooms – salons, a drawing room, a formal audience hall – all illuminated by fifty large windows, none protected by bars or iron grates, were centered around one overwhelming architectural oddity, the grandest, most formal stairway ever yet constructed in the west of Ireland.

Some idea as to the extraordinary nature of Eyre’s conception is the fact that this carefully contrived element occupied one-third of the entire house. There is no functionality to the design; no house or domestic dwelling requires that a staircase be so all consuming of its available space, if in fact the desire is utility. At Eyrecourt, the stairway was intended to make a statement: it conveyed power, ownership, pride, permanence, and sovereignty, none of these idle conceits. It seemed to say that battles, civil war, and discord were things of the past, that the political situation had been settled. Instead of military decorations, in fact, carvings of shields, swords, flags, cannon and the like, which were featured in contemporary examples in England such as Ham House in Richmond, Col. Eyre decided that more mundane decorative embellishments to this architectural statement be incorporated, such as bowls of fruit and acanthus leaves sprouting from the mouths of gargoyles.[2]

The entryway to the ground floor foyer was equally sumptuous, two oversized double-hung oak doors surrounded by six sleek pillars, richly carved, enclosing an oval window embrasure, itself surmounted by a rectangular frame, also highly ornamented, all protected by an overhanging portico with complicated molding. Inside the frame was carved the inscription, “Welcome to the House of Liberty,” an enigmatic slogan that confused the preacher John Wesley, who visited Eyrecourt on several occasions. “Does it mean liberty from sin?” he jotted in his journal.[3]

Entering the house through a small entry “box” (to protect the hall from gusting winds) Wesley, among others, would have seen, firstly, a large elaborately carved representation of the Eyre coat of arms; and then, in all its glory, two monumental sets of stairs on either side of the hallway, each leading to a pair of landings, the second of which would then turn 180 degrees and form a single flight of final stairs via yet another landing.

The objective for all who climbed this great staircase was the piano nobile, Italian for “noble floor,” the highlight of which was the main reception room where guests (or supplicants) could be greeted with some ceremony amid splendid surroundings, there to be entertained (or threatened as the case might be); in other words, the most important chamber in the house. As befits this status, it was guarded at Eyrecourt by an impressive set of doors flanked on either side by columns and then floor-to-ceiling panels stretching across the entire breadth of the stairwell. Overlooking the entire ensemble was a multi-paneled plaster ceiling, elaborately fashioned. It would appear that the exoticism of Florence, Ferrara, Lucca, Verona, and all the important Renaissance Italian cities, and in particular Venice, offered too many examples for English architects to ignore.[4] The lower floors were less emphasized, their role in daily life that of the ordinary such as bedrooms, offices, breakfast rooms and so forth. Usually, but not in the case of Eyrecourt, the windows of the piano nobile were large and more ornate than those of other floors.

Everywhere were carvings: noble pillars supporting the main mid-level “turnaround,” eighteen full dimensional fruit and flower bowls set atop the newel posts, with twelve half profiles inserted in the walls; and instead of simple balustrades connecting the hand railings with the floor of each riser, complicated panels with swirling decorative flourishes. At the top of the stairs, its richly carved doors and doorframes were seconded by wainscoting panels lining every other available piece of space on the walls. This ensemble of carefully designed and integrated elements would be worthy of any grand house in England. Given the setting here, an insignificant town in a backward and provincial Ireland where, according to Petty’s survey of 1672, four out of five dwellings in the country lacked a chimney (Eyrecourt had four), this installation beggars belief.[5] It also defies easy explanation.

William Randolph Hearst & The Eyrecourt Staircase

By James Charles Roy

Roughly ten miles south from the obscure East Galway town of Eyrecourt, off the Portumna Road, stand the well preserved remains of Derryhivenny Castle, constructed by one Daniel O’Madden in 1643, as a date chiseled into one of its remaining corbel stones tells us. Derryhivenny is not, in reality, a castle, but a fortified tower house, the likes of which form one of the most common relics of the Tudor and early Stuart eras in Ireland, representing as it does the unsettled times through which a man like O’Madden had to navigate. A landowner of considerable local stature, he sought from his home what others of his rank shared in common, a measure of protection from the turbulence that lay just outside his gated walls, as opposed to comfort.[1] A bare twenty years later, however, the Protestant Colonel John Eyre, a Cromwellian officer feasting on the spoils of military triumph, constructed his own “castle,” which he grandly christened Eyrecourt Castle. Despite the sometimes tenuous hold that English forces exercised over the countryside, and especially those lands west of the Shannon, Eyre evidently held a sanguine eye for the future. He constructed for himself and family (on lands once dominated by the aforementioned O’Maddens) a house built for pleasure. Instead of a high stone tower with narrow embrasures which barely passed as windows, and castellated ramparts from which inhabitants under siege could throw or shoot projectiles on enemies below, Eyrecourt Castle was a three-storey mansion without any pretense of a military function. Light, airy, grand rooms – salons, a drawing room, a formal audience hall – all illuminated by fifty large windows, none protected by bars or iron grates, were centered around one overwhelming architectural oddity, the grandest, most formal stairway ever yet constructed in the west of Ireland.

Some idea as to the extraordinary nature of Eyre’s conception is the fact that this carefully contrived element occupied one-third of the entire house. There is no functionality to the design; no house or domestic dwelling requires that a staircase be so all consuming of its available space, if in fact the desire is utility. At Eyrecourt, the stairway was intended to make a statement: it conveyed power, ownership, pride, permanence, and sovereignty, none of these idle conceits. It seemed to say that battles, civil war, and discord were things of the past, that the political situation had been settled. Instead of military decorations, in fact, carvings of shields, swords, flags, cannon and the like, which were featured in contemporary examples in England such as Ham House in Richmond, Col. Eyre decided that more mundane decorative embellishments to this architectural statement be incorporated, such as bowls of fruit and acanthus leaves sprouting from the mouths of gargoyles.[2]

The entryway to the ground floor foyer was equally sumptuous, two oversized double-hung oak doors surrounded by six sleek pillars, richly carved, enclosing an oval window embrasure, itself surmounted by a rectangular frame, also highly ornamented, all protected by an overhanging portico with complicated molding. Inside the frame was carved the inscription, “Welcome to the House of Liberty,” an enigmatic slogan that confused the preacher John Wesley, who visited Eyrecourt on several occasions. “Does it mean liberty from sin?” he jotted in his journal.[3]

Entering the house through a small entry “box” (to protect the hall from gusting winds) Wesley, among others, would have seen, firstly, a large elaborately carved representation of the Eyre coat of arms; and then, in all its glory, two monumental sets of stairs on either side of the hallway, each leading to a pair of landings, the second of which would then turn 180 degrees and form a single flight of final stairs via yet another landing.

The objective for all who climbed this great staircase was the piano nobile, Italian for “noble floor,” the highlight of which was the main reception room where guests (or supplicants) could be greeted with some ceremony amid splendid surroundings, there to be entertained (or threatened as the case might be); in other words, the most important chamber in the house. As befits this status, it was guarded at Eyrecourt by an impressive set of doors flanked on either side by columns and then floor-to-ceiling panels stretching across the entire breadth of the stairwell. Overlooking the entire ensemble was a multi-paneled plaster ceiling, elaborately fashioned. It would appear that the exoticism of Florence, Ferrara, Lucca, Verona, and all the important Renaissance Italian cities, and in particular Venice, offered too many examples for English architects to ignore.[4] The lower floors were less emphasized, their role in daily life that of the ordinary such as bedrooms, offices, breakfast rooms and so forth. Usually, but not in the case of Eyrecourt, the windows of the piano nobile were large and more ornate than those of other floors.

Everywhere were carvings: noble pillars supporting the main mid-level “turnaround,” eighteen full dimensional fruit and flower bowls set atop the newel posts, with twelve half profiles inserted in the walls; and instead of simple balustrades connecting the hand railings with the floor of each riser, complicated panels with swirling decorative flourishes. At the top of the stairs, its richly carved doors and doorframes were seconded by wainscoting panels lining every other available piece of space on the walls. This ensemble of carefully designed and integrated elements would be worthy of any grand house in England. Given the setting here, an insignificant town in a backward and provincial Ireland where, according to Petty’s survey of 1672, four out of five dwellings in the country lacked a chimney (Eyrecourt had four), this installation beggars belief.[5] It also defies easy explanation.

Whose idea was it to pursue such a complicated design, Col. Eyre’s, a professional soldier and then politician, or his wife, a woman with a French Huguenot background and, perhaps, social ambition? Whom did they hire to come up with the plan, some itinerant foreigner recommended by someone else (surely not a local “architect”)? Where did the carvers come from? Probably not from the local population, although the notion of apprentices from the area is not farfetched, given Ireland’s long history of superior stone carvers. Were these craftsmen English, Dutch, Flemish, French or Italian? Hints and suggestive leads exist, to be sure, but definitive answers are likely to elude us.

Along with these series of question marks, and contributing to the sense of irony that envelopes much of Eyrecourt’s long story, how did it happen that this singular creation has, for nearly one hundred years, sat disassembled in dozens of crates and, since 1951, been parked in a storage facility in suburban Detroit, Michigan? How did fate decree this, and what does its future hold?

The Eyre Family

It is intriguing to ruminate at the sense of optimism that a man such as Col. Eyre must have entertained to go through a building project of this sort and at this particular time in Ireland’s history. He had come to the island as a veteran of Cromwell’s New Model Army; he had lived through the uncertainties of civil war, the execution of a king, the varying and day-by-day switching of allegiances that the rush of political affairs often forced on its participants, followed by the return of the Stuarts who had what on their minds? Revenge, perhaps, the desire to see those punished who had cut off the head of a duly anointed monarch, the urge to strip those of uncertain loyalty of their lands, titles, wealth, and even lives. What possessed John Eyre to build anything other than a fortress, a stronghold, a redoubt surrounded by walls, instead of what he did commission, an open great house with windows, light and air, in a demesne or park without fortified gates or defensive works? This cannot logically be explained. Whose side would he have been on, for example, had he lived for another five years to 1690, when William of Orange came to Ireland to grapple with another divine right king, James II (undoubtedly William, one would suppose, but surprises always raise their heads during confusing times such as these; James Fitz James Butler, 2nd duke of Ormond, a Protestant and a combatant for the Willamette forces at the Boyne, was attainted for treason in 1715 for his involvement in Catholic Jacobite conspiracies, so stranger things have happened).[6]

The events of Col. Eyre’s career have been capably treated in this journal, and do not require repeating in detail here.[7] Family historians unearthed several colorful and self-serving explanations for the origin of their name, many revolving around the Battle of Hastings in 1066, in which a forbearer fought under the name Truelove. It is related that when William the Conqueror was unhorsed during the fray, the nose guard of his helmet jammed into his face and had to be wrested free, allowing him to gasp for air (hence Eyre). The stalwart who performed that feat, and then helped the conqueror back into his saddle, lost a leg later in the fight, which helpfully explains the device at the top of the Eyre coat of arms, a leg cooped at the upper thigh (cooped is a heraldic term meaning “clean cut off.”) Other versions have the Eyre in question becoming an amputee in the service of Richard the Lion Heart, thereby throwing the entire story into the realm of apocrypha, but it seems that at some point an ancestor from the past gave suitable service to his king and was rewarded for it.[8]

John Eyre, to his misfortune, was the seventh son of ten in his family, and could predict little good fortune remaining in Wiltshire, England, where he was born at some unknown date. He and another younger son, Edward, were military men, and had likely joined a company of horse sent to Ireland in January of 1651 as reinforcements to the original army that had landed with Cromwell the previous year. Both these young men belonged to bands recruited in their native county and under the command of the noted regicide, Sir Edmund Ludlow, also a Wiltshire man. They were, as Ludlow wrote in his memoirs, armed with “back, breast, and head pieces, pistols and musketoons, with two months pay advanced.”[9] Landing in Duncannon, a few miles from Waterford, they participated in the siege of Limerick and the later mop-up campaign in Connaught, the royalists then under the dispirited leadership of Ulick Burke, fifth earl of Clanricard, which culminated in the fall of Galway City in April, 1652, where both Eyres were present. In the long and complicated maneuverings thereafter, as parliament attempted to figure out how to pay men such as these for their services, the “coin” of the moment became land. Both brothers received substantial grants both in the city itself and outlying portions of the province, augmented no doubt with purchases from fellow soldiers who had no wish to remain in Ireland.

Edward Eyre, and to a less extent his brother, became heavily involved, both politically and commercially, within the city walls (Eyre Square is a reminder of their presence, and Edward’s numerous feuds with the Martin family have been well established). But Col. John Eyre’s principal interests lay in the accumulation of farm and grazing lands in the eastern portion of the county, where his dexterity in figuring out how to handle the return of the Stuarts is a testament to his abilities. By the time of his death in 1685, he held properties in four counties, with most of his holdings centered around the “plantation” village he more or less created, Eyrecourt. His vision there can best be summarized by the privileges he was able to wheedle from the government of Charles II: a grant to establish a walled demesne and deer park of 500 acres, the right to hold biannual fairs and a weekly market, a monopoly on local police powers, permission to build a goal, and so on. Over time a regularized “mall” was envisioned, with a courthouse and other public amenities, which remain today off the main road through the village. In 1732, the indefatigable letter writer Mary Granville (Mrs. Delaney), after “jogging on through bogs and over plains,” noted approvingly that the “improvements looked very English;” and John Wesley wrote that the market house, where he preached, was “a large and handsome room,” reminders that Eyre had greater plans for this formerly unremarkable place then anything his successors eventually accomplished.[10] A member of the Irish parliament and in charge of several important royal commissions, Eyre served as a privy councilor for the last three years of his life. In the midst of this busy and, it would appear, productive life, Eyre built his “castle,” the year of which is unknown with certainty, but 1661 seems generally correct.

From available evidence, whatever artistic spirit Col. John Eyre exhibited when he built Eyrecourt Castle did not translate with any consistency into the behavior of his descendants. When the Irish political environment settled down after 1715, many gentlemen of the upper classes, whether nouveau or long lineaged, often took themselves to the continent, and especially Italy, to further both their educations and their accumulation of art treasures. In architecture, Ireland saw the construction of several Palladian style mansions, best exampled by William Conolly’s spectacular Castletown (begun 1722), and the flourishing of Irish creativity in the decorative arts throughout the country on various landed estates, particularly those close to Dublin. Eyrecourt, it seems, stood aside from such developments. The fifth in succession to Col Eyre, and also named John, held the usual offices to which the country gentry of Galway customarily aspired: member of parliament for two decades (beginning in 1747), sheriff of the county (1752), admitted to the bar (1754), followed by elevation to the peerage in 1768 as Baron Eyre of Eyrecourt, undoubtedly the work of George Townshend, the deeply unpopular viceroy from 1767 to 1772. Townshend’s portfolio from George III was to reform Ireland, to free its legislative processes from the often grotesque requirements of bribery and patronage (little better than “continual blackmail,” according to one historian), and to augment the manpower levels of Irish regiments, to be paid for locally, and not from England. All of these London-based goals were offensive, insulting, and threatening to the Irish Protestant elite, and to counterbalance their influence Townshend resorted to rewards of his own to sympathetic parliamentarians who came to be known as the “Castle party.” Eyre, considered a “serviceable member of the late House,” was one of these, and an earldom the result.[11]

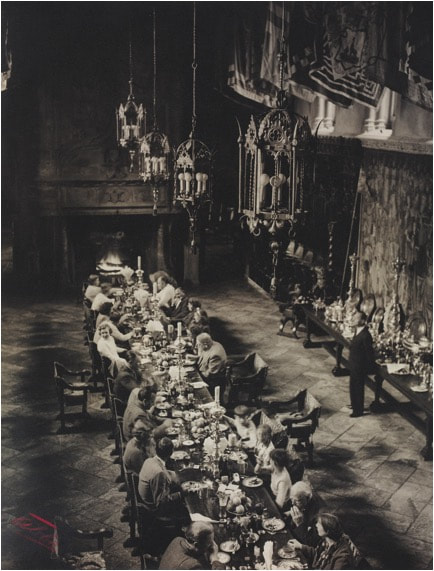

Eyre was not an overly bookish man. Some letters survive, mostly written in his years of semiretirement, and these are well styled for the most part. He was contemptuous of the political environment in Ireland. The Irish parliament was little better than a den of thieves, in his opinion. In the House of Lords, “it astonished me to find men with one leg in the grave, as open to corruption, and as eager in pursuit of worldly advantages as if they were fifteen – nay, even among the hoary Bench of Bishops;” and as for local affairs, I “wish Galway was sunk in the sea.”[12] The dramatist Richard Cumberland recounted a visit to Eyrecourt c. 1770 (Cumberland’s father was bishop of Clonfert, whom he often visited, though it was surrounded by “impenetrable bog [and] dreary, undressed country”). He portrayed Eyre as a gentlemen, generous to a fault, but indolent, sitting in a chair all day “sipping wine,” a process “carried on with very little aid from conversation, for his lordship’s companions were not very communicative, and fortunately he was not very curious.” Cumberland also noted that Eyre had never “been out of Ireland in his life” (certainly not true), and that a trip they took together to visit a neighbor at nearby Mount Talbot was about as far as Eyre had been in years. This was not a man apt to travel to Rome, in other words, or to marvel at the great examples of classical architecture, paintings or tapestries. To be honest, it seems that Cumberland, was writing for effect, composing a charming portrait of an idiosyncratic and harmless member of the local gentry whose only real obsession was cock fighting. But he also noted the poor state of local agriculture – Eyre owned “a vast extent of soil, not very productive” – and also, ominously, his “spacious mansion, not in the best repair.”[13] The preacher John Wesley, who stopped in Eyrecourt at least eight times between 1749 and 1787 to hector the faithful, was impressed by Lord Eyre’s “noble old house,” especially the staircase (“grand”) and “two or three of the rooms,” but he also observed that the outhouses and grounds were in “ruinous” condition.[14] The seeds of this family’s gradual decline, so familiar to many other country estates, is thus plainly stated: poorly run agricultural domains, large and difficult-to-maintain great houses, all undercut by famously generous hosts indulging themselves in the country pursuits of field sports and social largess, summed up by what Cumberland called “more hospitality than elegance,” the dinner table “groaning with abundance.”[15]

The Eyre peerage went extinct at his death in 1781, when a nephew, one Giles Eyre, inherited the estate, heavily encumbered “in consequence of [Baron Eyre’s] electioneering tendencies, and other similar propensities,” but still enjoying an annual rent roll of £20,000.[16] So ghastly were Eyrecourt’s finances that Giles was unable to take up residence in the “castle” for some fifteen or so years, when one of the family’s major creditors, one Michael Prendergast, took possession as payment in kind.[17] Nonetheless, Giles made the situation incomparably worse with his own spectacular extravagancy upon his accession (he too spent lavishly trying to win a seat in parliament, said to have cost him in an 1811 contest some £80,000).[18] An English visitor who met Eyre noted in a privately published memoir two-well traveled themes when it came to describing the gentry of rural Ireland. In the first, that Giles Eyre was “evidently getting tired [of his patrimony], for like his neighbors, he was doing all he could to send it to the winds; he could barely write, and yet he contrived to sign his name to as many bonds … as would thatch Lough Cutra Castle.” The second was the addiction to field sports. “Hunting, fishing, shooting, drinking were his accomplishments,” he wrote. Eyre and his loutish friends, by “their violent and constant exercise by day occasioned them to take a booze at night, separating seldom till the dawn of day appeared, when the hounds and horses were all in readiness once more, so that t’was difficult, as many may well suppose, to distinguish one day from another.”[19] It was either the baron or Giles who built the enormous stables adjacent to the main house (and not to the rear, as in most instances), where Giles kept his own pack of hounds (precursor to those of the famous Galway Blazers, of which he was master from 1791 to 1829) and, it is said, from 30 to 40 hunters.[20] One is reminded here of county priorities, best exemplified by the inscription still to be seen over the archway to the stables of Dromoland Castle in County Clare, In equus partum virius (“The strength of a nation is in its horses”).[21] Charles Lever memorialized Eyre in one of his better known lines, “Ould Giles Eyre/Would make them stare,” a phrase the owner of Dooley’s Hotel in Birr would remember for years, after Eyre and a group of his rowdy friends started a fire on the premises which burned the place down (hence the origin, allegedly, of the moniker attached to the famous hunt, the “Blazers”).[22] Giles’s son and heir, another enthusiastic rider to the hounds, was killed in the winter of 1856 after taking a spill and breaking his neck, which enveloped the entire town “in a cloud of gloom.” His funeral, watched by a reported crowd of 6,000 (surely an exaggeration), was attended by the usual array of local gentry, i.e. Dalys, Moores, Lyons, Persses, Blakes, Ushers and so on. “He died at the mellowed but still hearty age of sixty-one,” according to a county newspaper.[23]

Eyre cousins and cadet branches were no better. Samuel Eyre of Eyreville, seven miles to the west, who died 1788, was described as an “idle, extravagant and reckless man, paying no attention to the family inheritance.”[24] The tales and travels of younger sons, with no immediate future in Ireland, followed the usual pattern over successive generations: military careers in far-flung outposts of the empire (and beyond) – Sudan, South Africa, India, Crimea, the West Indies, even action in the South American wars of independence – or office jobs in London, New York, and any number of small towns scattered throughout the British Isles, to say nothing of Australia and New Zealand. The profligacy of the various Eyrecourt Eyres resulted in the remainder of the estate being put up for sale in 1854, a division into 33 lots, in the hopes that £40,000 in debt could be resolved. By the time the auctioneer’s gavel reached # 26, the sum had been raised, the great house saved (“a hearty cheer burst from several of [Eyre’s] tenantry who were at the court”), but with such a diminished rent roll that supporting the old grand life style became next to impossible, if the situation were to be viewed factually.[25]

Along with these series of question marks, and contributing to the sense of irony that envelopes much of Eyrecourt’s long story, how did it happen that this singular creation has, for nearly one hundred years, sat disassembled in dozens of crates and, since 1951, been parked in a storage facility in suburban Detroit, Michigan? How did fate decree this, and what does its future hold?

The Eyre Family

It is intriguing to ruminate at the sense of optimism that a man such as Col. Eyre must have entertained to go through a building project of this sort and at this particular time in Ireland’s history. He had come to the island as a veteran of Cromwell’s New Model Army; he had lived through the uncertainties of civil war, the execution of a king, the varying and day-by-day switching of allegiances that the rush of political affairs often forced on its participants, followed by the return of the Stuarts who had what on their minds? Revenge, perhaps, the desire to see those punished who had cut off the head of a duly anointed monarch, the urge to strip those of uncertain loyalty of their lands, titles, wealth, and even lives. What possessed John Eyre to build anything other than a fortress, a stronghold, a redoubt surrounded by walls, instead of what he did commission, an open great house with windows, light and air, in a demesne or park without fortified gates or defensive works? This cannot logically be explained. Whose side would he have been on, for example, had he lived for another five years to 1690, when William of Orange came to Ireland to grapple with another divine right king, James II (undoubtedly William, one would suppose, but surprises always raise their heads during confusing times such as these; James Fitz James Butler, 2nd duke of Ormond, a Protestant and a combatant for the Willamette forces at the Boyne, was attainted for treason in 1715 for his involvement in Catholic Jacobite conspiracies, so stranger things have happened).[6]

The events of Col. Eyre’s career have been capably treated in this journal, and do not require repeating in detail here.[7] Family historians unearthed several colorful and self-serving explanations for the origin of their name, many revolving around the Battle of Hastings in 1066, in which a forbearer fought under the name Truelove. It is related that when William the Conqueror was unhorsed during the fray, the nose guard of his helmet jammed into his face and had to be wrested free, allowing him to gasp for air (hence Eyre). The stalwart who performed that feat, and then helped the conqueror back into his saddle, lost a leg later in the fight, which helpfully explains the device at the top of the Eyre coat of arms, a leg cooped at the upper thigh (cooped is a heraldic term meaning “clean cut off.”) Other versions have the Eyre in question becoming an amputee in the service of Richard the Lion Heart, thereby throwing the entire story into the realm of apocrypha, but it seems that at some point an ancestor from the past gave suitable service to his king and was rewarded for it.[8]

John Eyre, to his misfortune, was the seventh son of ten in his family, and could predict little good fortune remaining in Wiltshire, England, where he was born at some unknown date. He and another younger son, Edward, were military men, and had likely joined a company of horse sent to Ireland in January of 1651 as reinforcements to the original army that had landed with Cromwell the previous year. Both these young men belonged to bands recruited in their native county and under the command of the noted regicide, Sir Edmund Ludlow, also a Wiltshire man. They were, as Ludlow wrote in his memoirs, armed with “back, breast, and head pieces, pistols and musketoons, with two months pay advanced.”[9] Landing in Duncannon, a few miles from Waterford, they participated in the siege of Limerick and the later mop-up campaign in Connaught, the royalists then under the dispirited leadership of Ulick Burke, fifth earl of Clanricard, which culminated in the fall of Galway City in April, 1652, where both Eyres were present. In the long and complicated maneuverings thereafter, as parliament attempted to figure out how to pay men such as these for their services, the “coin” of the moment became land. Both brothers received substantial grants both in the city itself and outlying portions of the province, augmented no doubt with purchases from fellow soldiers who had no wish to remain in Ireland.

Edward Eyre, and to a less extent his brother, became heavily involved, both politically and commercially, within the city walls (Eyre Square is a reminder of their presence, and Edward’s numerous feuds with the Martin family have been well established). But Col. John Eyre’s principal interests lay in the accumulation of farm and grazing lands in the eastern portion of the county, where his dexterity in figuring out how to handle the return of the Stuarts is a testament to his abilities. By the time of his death in 1685, he held properties in four counties, with most of his holdings centered around the “plantation” village he more or less created, Eyrecourt. His vision there can best be summarized by the privileges he was able to wheedle from the government of Charles II: a grant to establish a walled demesne and deer park of 500 acres, the right to hold biannual fairs and a weekly market, a monopoly on local police powers, permission to build a goal, and so on. Over time a regularized “mall” was envisioned, with a courthouse and other public amenities, which remain today off the main road through the village. In 1732, the indefatigable letter writer Mary Granville (Mrs. Delaney), after “jogging on through bogs and over plains,” noted approvingly that the “improvements looked very English;” and John Wesley wrote that the market house, where he preached, was “a large and handsome room,” reminders that Eyre had greater plans for this formerly unremarkable place then anything his successors eventually accomplished.[10] A member of the Irish parliament and in charge of several important royal commissions, Eyre served as a privy councilor for the last three years of his life. In the midst of this busy and, it would appear, productive life, Eyre built his “castle,” the year of which is unknown with certainty, but 1661 seems generally correct.

From available evidence, whatever artistic spirit Col. John Eyre exhibited when he built Eyrecourt Castle did not translate with any consistency into the behavior of his descendants. When the Irish political environment settled down after 1715, many gentlemen of the upper classes, whether nouveau or long lineaged, often took themselves to the continent, and especially Italy, to further both their educations and their accumulation of art treasures. In architecture, Ireland saw the construction of several Palladian style mansions, best exampled by William Conolly’s spectacular Castletown (begun 1722), and the flourishing of Irish creativity in the decorative arts throughout the country on various landed estates, particularly those close to Dublin. Eyrecourt, it seems, stood aside from such developments. The fifth in succession to Col Eyre, and also named John, held the usual offices to which the country gentry of Galway customarily aspired: member of parliament for two decades (beginning in 1747), sheriff of the county (1752), admitted to the bar (1754), followed by elevation to the peerage in 1768 as Baron Eyre of Eyrecourt, undoubtedly the work of George Townshend, the deeply unpopular viceroy from 1767 to 1772. Townshend’s portfolio from George III was to reform Ireland, to free its legislative processes from the often grotesque requirements of bribery and patronage (little better than “continual blackmail,” according to one historian), and to augment the manpower levels of Irish regiments, to be paid for locally, and not from England. All of these London-based goals were offensive, insulting, and threatening to the Irish Protestant elite, and to counterbalance their influence Townshend resorted to rewards of his own to sympathetic parliamentarians who came to be known as the “Castle party.” Eyre, considered a “serviceable member of the late House,” was one of these, and an earldom the result.[11]

Eyre was not an overly bookish man. Some letters survive, mostly written in his years of semiretirement, and these are well styled for the most part. He was contemptuous of the political environment in Ireland. The Irish parliament was little better than a den of thieves, in his opinion. In the House of Lords, “it astonished me to find men with one leg in the grave, as open to corruption, and as eager in pursuit of worldly advantages as if they were fifteen – nay, even among the hoary Bench of Bishops;” and as for local affairs, I “wish Galway was sunk in the sea.”[12] The dramatist Richard Cumberland recounted a visit to Eyrecourt c. 1770 (Cumberland’s father was bishop of Clonfert, whom he often visited, though it was surrounded by “impenetrable bog [and] dreary, undressed country”). He portrayed Eyre as a gentlemen, generous to a fault, but indolent, sitting in a chair all day “sipping wine,” a process “carried on with very little aid from conversation, for his lordship’s companions were not very communicative, and fortunately he was not very curious.” Cumberland also noted that Eyre had never “been out of Ireland in his life” (certainly not true), and that a trip they took together to visit a neighbor at nearby Mount Talbot was about as far as Eyre had been in years. This was not a man apt to travel to Rome, in other words, or to marvel at the great examples of classical architecture, paintings or tapestries. To be honest, it seems that Cumberland, was writing for effect, composing a charming portrait of an idiosyncratic and harmless member of the local gentry whose only real obsession was cock fighting. But he also noted the poor state of local agriculture – Eyre owned “a vast extent of soil, not very productive” – and also, ominously, his “spacious mansion, not in the best repair.”[13] The preacher John Wesley, who stopped in Eyrecourt at least eight times between 1749 and 1787 to hector the faithful, was impressed by Lord Eyre’s “noble old house,” especially the staircase (“grand”) and “two or three of the rooms,” but he also observed that the outhouses and grounds were in “ruinous” condition.[14] The seeds of this family’s gradual decline, so familiar to many other country estates, is thus plainly stated: poorly run agricultural domains, large and difficult-to-maintain great houses, all undercut by famously generous hosts indulging themselves in the country pursuits of field sports and social largess, summed up by what Cumberland called “more hospitality than elegance,” the dinner table “groaning with abundance.”[15]

The Eyre peerage went extinct at his death in 1781, when a nephew, one Giles Eyre, inherited the estate, heavily encumbered “in consequence of [Baron Eyre’s] electioneering tendencies, and other similar propensities,” but still enjoying an annual rent roll of £20,000.[16] So ghastly were Eyrecourt’s finances that Giles was unable to take up residence in the “castle” for some fifteen or so years, when one of the family’s major creditors, one Michael Prendergast, took possession as payment in kind.[17] Nonetheless, Giles made the situation incomparably worse with his own spectacular extravagancy upon his accession (he too spent lavishly trying to win a seat in parliament, said to have cost him in an 1811 contest some £80,000).[18] An English visitor who met Eyre noted in a privately published memoir two-well traveled themes when it came to describing the gentry of rural Ireland. In the first, that Giles Eyre was “evidently getting tired [of his patrimony], for like his neighbors, he was doing all he could to send it to the winds; he could barely write, and yet he contrived to sign his name to as many bonds … as would thatch Lough Cutra Castle.” The second was the addiction to field sports. “Hunting, fishing, shooting, drinking were his accomplishments,” he wrote. Eyre and his loutish friends, by “their violent and constant exercise by day occasioned them to take a booze at night, separating seldom till the dawn of day appeared, when the hounds and horses were all in readiness once more, so that t’was difficult, as many may well suppose, to distinguish one day from another.”[19] It was either the baron or Giles who built the enormous stables adjacent to the main house (and not to the rear, as in most instances), where Giles kept his own pack of hounds (precursor to those of the famous Galway Blazers, of which he was master from 1791 to 1829) and, it is said, from 30 to 40 hunters.[20] One is reminded here of county priorities, best exemplified by the inscription still to be seen over the archway to the stables of Dromoland Castle in County Clare, In equus partum virius (“The strength of a nation is in its horses”).[21] Charles Lever memorialized Eyre in one of his better known lines, “Ould Giles Eyre/Would make them stare,” a phrase the owner of Dooley’s Hotel in Birr would remember for years, after Eyre and a group of his rowdy friends started a fire on the premises which burned the place down (hence the origin, allegedly, of the moniker attached to the famous hunt, the “Blazers”).[22] Giles’s son and heir, another enthusiastic rider to the hounds, was killed in the winter of 1856 after taking a spill and breaking his neck, which enveloped the entire town “in a cloud of gloom.” His funeral, watched by a reported crowd of 6,000 (surely an exaggeration), was attended by the usual array of local gentry, i.e. Dalys, Moores, Lyons, Persses, Blakes, Ushers and so on. “He died at the mellowed but still hearty age of sixty-one,” according to a county newspaper.[23]

Eyre cousins and cadet branches were no better. Samuel Eyre of Eyreville, seven miles to the west, who died 1788, was described as an “idle, extravagant and reckless man, paying no attention to the family inheritance.”[24] The tales and travels of younger sons, with no immediate future in Ireland, followed the usual pattern over successive generations: military careers in far-flung outposts of the empire (and beyond) – Sudan, South Africa, India, Crimea, the West Indies, even action in the South American wars of independence – or office jobs in London, New York, and any number of small towns scattered throughout the British Isles, to say nothing of Australia and New Zealand. The profligacy of the various Eyrecourt Eyres resulted in the remainder of the estate being put up for sale in 1854, a division into 33 lots, in the hopes that £40,000 in debt could be resolved. By the time the auctioneer’s gavel reached # 26, the sum had been raised, the great house saved (“a hearty cheer burst from several of [Eyre’s] tenantry who were at the court”), but with such a diminished rent roll that supporting the old grand life style became next to impossible, if the situation were to be viewed factually.[25]

The entryway c. 1950s, everything stripped away save the ruinous door panels

The entryway c. 1950s, everything stripped away save the ruinous door panels

The Eyres, however, seem to have been genetically sealed from reality, various press reports describing lavish entertainments.[26] In 1883 the house and demesne were again offered for sale in the Land Judges Court. By this time Eyre-controlled properties all over the county were being placed for sale (notices occur in 1857, 1869, 1870, and 1872). The Eyre of the moment holding Eyreville, the second largest of the family holdings, was described as “an insolvent debtor” when that estate was brought to market in 1883.[27] A privately printed history of the family, published fifteen years later, noted that the then current scion of Eyrecourt, one William Henry Gregory Eyre, “is a young man, and having started for himself in America as a mere boy, is full of mettle and go, having no nonsense about him, and he may yet retrieve the fallen fortunes of his family.”[28] At his death in 1925, however, he had become a caricature of sorts, the Anglo-Irish landlord “hanging on to a hulk of a house” with a diminished demesne, the remaining property having dwindled to a mere 620 acres, with paltry rents to match, not much to show from the heyday of this family’s fortunes when the Eyrecourt portfolio numbered over “30,000 green acres,” plus bog and mountain.[29]

What all these decades of declining cash flow, along with the rough and tumble antics of nearly two hundred years habitation by a riotous mélange of sport enthusiasts, meant to the fabric of Eyrecourt Castle must largely be imagined, as the condition of the main house was rarely mentioned in contemporary news accounts, diaries, or letters still extant. Our only clues are few. On the one hand, we have the idealized version, a pen and ink study of the stairway ensemble done by Lady Gregory (née Augusta Persse, of Roxborough House) c. 1888, and previously reproduced in this journal.[30] This time frame represents the beginning of Lady Gregory’s habit of sketching and painting historical subjects, especially those of local interest, which approximately coincides with her first attempts to learn Irish. Undoubtedly influenced by her husband, Sir William Gregory, whose interest in historic architecture and archeology was catholic in its wide range, Lady Gregory portrayed several sites in her Galway neighborhood, from Big Houses, Thoor Ballylee (purchased by W. B. Yeats in 1917), scenes from the Aran Islands, the round tower of Kilmacduagh (whose restoration William Gregory helped fund) and, in her widowhood, English cathedrals, Stonehenge, and other spots further afield. There are a few perfunctory mentions of Eyrecourt in Lady Gregory’s extant letters or diaries, but she was surely familiar with the family and interconnected with them at the usual social amenities of her time and class, i.e. hunts, fairs, dances, weddings, dinners and so on. In the visitor’s book of Arthur Clive Guinness’s Ashford Castle dated c. 1870, the attendance of both Miss Alice Eyre of Eyrecourt, and Lady Gregory’s brother, Robert Algeron Gregory of Roxborough, is noted for a weeklong house party.[31] That Lady Gregory visited Eyrecourt on some occasion, and felt compelled to record its most outstanding feature, is hardly remarkable. The last “scion” of Eyrecourt, for example, William Henry Gregory Eyre, was clearly so named as an honor by his father to Lady Gregory’s husband.

By contrast, there are, fortunately, several period photographs of the staircase, though exactly when they were taken is unknown, but probably in the first decade of the twentieth century.[32] Eyrecourt certainly enjoyed some amenities; a radiator is visible in one exposure, and the house had been wired for electricity, as evinced by a lighting stanchion suspended from the ceiling with 8 globes (one broken and not replaced). While electrification was not a rarity in the British Isles, it was certainly not unusual to visit Ireland for a country week of shooting to find one’s domicile still illuminated by candles and oil lamps. Hatfield House, Lord Salisbury’s magnificent palace some twenty miles out of London, was wired in 1882, but missteps clouded many years of its early use and discouraged imitation: sparks were a daily occurrence, the entire system failed regularly, and a gardener was inadvertently electrocuted. As a general rule, the electrification of the British Isles enjoyed it greatest surge between the two world wars (in England, the number of users jumped from 750,000 to 9 million in just twenty years, a trend duplicated, in much smaller numbers, in Ireland). Eyrecourt Castle, at least in this respect, was slightly ahead of the curve.[33]

But closer examination of these photographic images reveal a house well in the midst of its decline. A grouping of oriental rugs at the foot of the staircase appear shabby and frayed. The regal front doorway, so typical of Irish houses to this day, is enshrouded by an inner enclosure, a barrier to cold winds flying in from the west. The walls to the left and right of the first set of parallel stairs rising to the next landing show a few portraits and framed images but not, as is usual in British houses of similar pedigree, layered in rows from floor to ceiling (as has been commonly asserted, when a landed family fell into financial disarray, the first things sold were the contents of the library, if there was one, and then whatever artwork might be around).[34]

The stairway looking down from the second landing to foyer and entryway.

The stairway looking down from the second landing to foyer and entryway.

Study of the staircase reveals nicks, scratches, gouges, scuffing, and other marks of rough usage as well as, in the Knight of Glin’s phraseology, hints of “slovenly housekeeping.”[35] But most revealing is evidence that the staircase appears to have been stained (several years previously) with a black or brown veneer. When initially installed and as a final fillip, the wood may well have been marbled or similarly “veined” and then, possibly, gilded, a commonly used (and expensive) touch that has precedence in late seventeenth century decorative practice. That it was stained would appear to reflect the worsening financial condition of the Eyre family, who found the structure in need of reconditioning but unable to afford an accurate restoration, i.e. a dash of paint would do the job. It will be difficult to prove this supposition definitively, as the stairway’s second owner, William Randolph Hearst, had the entire structure stripped to the bare wood, perhaps in anticipation of a thorough rejuvenation to its original splendor.

The Mansion and its Staircase

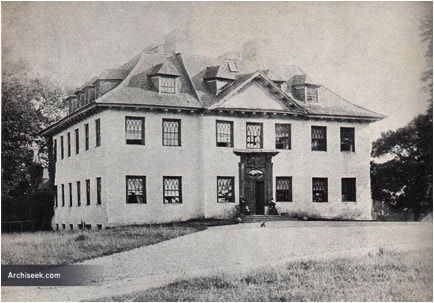

A period photograph of Eyrecourt Castle from the late nineteenth century, with two ladies dressed in black seated on either side of the monumental doorway, is the best guide available to the somewhat idiosyncratic nature of the building’s construction. The façade presented seven bays of windows, three over the front door, covered by a wide triangular overhang supported by nine carved corbels, anchored on each end by dormer windows. The hip-roof is tilted as it descends (or “stacketed”), a common feature from the continent, i.e., titled upwards, giving the profile “a frivolous elegance,” and not a feature one would expect from this time period in the west of Ireland. The entire roof is also supported by ninety-eight corbels, all carved (presumably by the same workmen who did the staircase), as are the wooden frames for the windows. The Gothic tracery of the windowpanes themselves is allegedly of later workmanship, when the original window casings were replaced.[36]

Detailing the origins of the stairway’s design and execution, with its exceptionally fine carving, now enters the realm of speculation. There are clues and timelines to investigate, but any certainty as regards attribution, exact dating, or primary sources cannot be proven barring, of course, the discovery of hitherto unknown estate records, a dubious prospect given the Eyre family’s decline in County Galway and dispersion to the four corners of the globe.

The Mansion and its Staircase

A period photograph of Eyrecourt Castle from the late nineteenth century, with two ladies dressed in black seated on either side of the monumental doorway, is the best guide available to the somewhat idiosyncratic nature of the building’s construction. The façade presented seven bays of windows, three over the front door, covered by a wide triangular overhang supported by nine carved corbels, anchored on each end by dormer windows. The hip-roof is tilted as it descends (or “stacketed”), a common feature from the continent, i.e., titled upwards, giving the profile “a frivolous elegance,” and not a feature one would expect from this time period in the west of Ireland. The entire roof is also supported by ninety-eight corbels, all carved (presumably by the same workmen who did the staircase), as are the wooden frames for the windows. The Gothic tracery of the windowpanes themselves is allegedly of later workmanship, when the original window casings were replaced.[36]

Detailing the origins of the stairway’s design and execution, with its exceptionally fine carving, now enters the realm of speculation. There are clues and timelines to investigate, but any certainty as regards attribution, exact dating, or primary sources cannot be proven barring, of course, the discovery of hitherto unknown estate records, a dubious prospect given the Eyre family’s decline in County Galway and dispersion to the four corners of the globe.

Flower ensemble, decorative head of a newel post. Exceedingly heavy.

Flower ensemble, decorative head of a newel post. Exceedingly heavy.

The notion of a grand staircase was certainly not an innovation as such. The winding stairs of a castle tower were no longer the architectural vogue of the early seventeenth century, as domestic architecture in Ireland began its evolution from purely military function to one of more graceful living. First examples of what, for want of better terminology, might be labeled the “Eyrecourt design,” had numerous antecedents in England, the earliest in stone, but the unwieldy weight of such structures saw a quick transition to wood, and largely of oak construction. While the vogue in “great halls” of the medieval sort was fading during this era,[37] the notion of a receiving salon of suitable grandeur was not, and the prevailing norm came to be that such a space would not be on the ground floor, but the one above it. The approach, therefore, had to match the expected solemnity of the main chamber in the house. In Great Britain, ornate staircases to the piano nobile grew more common and substantially more ornate as the century progressed. Staircases were broad, the steps themselves of less height than the old solid stone blocks used in castles and tower houses, and turn-about landings, leading to the next cascade of steps, a common feature (Eyrecourt features four “landings,” one of which is the main turn-around). Decorative flourishes mostly concentrated on the tops of newel posts (where plain acorn style sculptures were soon surpassed by growingly elaborate fruit and flower based carvings), wainscoting and, particularly, in panels which replaced simple balustrade poles. These grew especially florid, as Eyrecourt exemplified. Reaching the entryway to the formal room, the visitor would be greeted by a formal set of doors, usually flanked by a set of pilasters, comprising a base, a shaft (often grooved), surmounted by a capital. In many cases, but not at Eyrecourt, these pillars would be decorated with that most favored Roman motif, acanthus leaves.

The acanthus is a perennial shrub, most diverse and common in the Mediterranean basin. Noted for its spiny, thickly veined leaves, early stonemasons in Greece and Asia Minor appreciated its decorative possibilities as a “drape” or curling form drooping downwards, and carved them into the capital heads of supporting pillars that came to be known by the adjective “Corinthian.” Roman designers expanded the device by adding a volute, or spiral scrolling, from the “Ionic” capital, thereby coming up with what architectural historians call the “Composite” (or “mixed”) order, a device seen everywhere in the western world, even today. The acanthus leaf, with its flowing form and sculptural characteristics, became a favorite of Renaissance, and then baroque woodcarvers in particular, as well as their patrons who looked to the classical world, and particularly Rome, as the fountainhead of art and culture.[38] At Eyrecourt, the acanthus motif is exuberantly displayed in the several panels inserted between the steps themselves and the handrails. These make the military decorations in the balustrade at Ham House in Great Britain, mentioned previously, seem banal by comparison, no matter the skill of carving displayed.

How and why would a Col. John Eyre, or his wife, be inspired by such designs? Or better yet, how would he ever have learned about them? Eyrecourt was reputedly built in the early 1660s, Col. Eyre then a man of probably middle age and entering the prime of his life, both physically and professionally. He was now a person of some consequence, certainly in County Galway and in Dublin, and possibly in London. The great era of classical building in Ireland, generally thought to have commenced under the duke of Ormond in 1680 (the Royal Hospital at Kilmainham) was still two decades into the future, likewise the extraordinary work of the Huguenot wood carver James Tabary and his two brothers, who worked on the exquisite altar piece that graces its chapel. The premier woodcarver of the seventeenth-century generation, Grinling Gibbons, a "myth encrusted figure” according to one art historian,[39] had not even landed in London from Rotterdam after the Great Fire of 1666 to begin his extraordinary career, so in all probability Col. Eyre had never heard of him; nor do we have any proof that Eyre returned to England after his Cromwellian beginnings in Ireland a decade before, during which he might have observed the work of a growing number of artisans, largely Protestant, who were emigrating to London from the continent in search of work or commissions. Possibly the most promising, if most uncertain explanation of Eyrecourt’s origins, might be “word of mouth,” a category ambiguously described by the Irish architectural historian R. Loeber as “less well defined influences.”[40]

Sir Roger Pratt, along with Christopher Wren an important figure in the development of professionalism in the field of British architecture, was known to have written tracts of advice and “principles” to guide both other designer/builders and those who might employ them, though the bulk of these remained unpublished at the time of his death in 1685. His reputation in court circles was considerable, as evinced by his appointment by Charles II to join Wren and Hugh May as commissioners to oversee the reconstruction of fire-ravaged central London in 1666, for which he received a knighthood.[41] In one of his piquant observations, written perhaps to advise country gentlemen who might doubt their own abilities or inclinations when it came to envisioning the construction of a seat, Pratt noted firstly, to “resolve with yourself what house will be answerable to your purse and estate … then if you be not able to handsomely contrive it yourself, get some ingenious gentleman who has seen much of that kind abroad and been somewhat versed in the best authors of Architecture: viz. Palladio, Scamozzi, Serlio etc. to do it for you, and to give you a design of it in paper.”[42] Such shadowy figures as these, i.e. “some ingenious gentlemen,” might have a satchel of drawings, elevations, sketches, or profiles of their own designs to pour over with a potential client, or a booklet of engravings or plates depicting examples from ancient Rome or, perhaps, representations of newly famous buildings, such as the town hall of Amsterdam, begun in 1648. These were ready-made to adapt, copy, or alter as circumstances (or one’s financial circumstances) might allow. It is interesting to note that Pratt was best known for producing buildings that seem, at first glance, remarkably similar to Eyrecourt: hipped roofs, dormer windows, a surround walkway for views, half- windows on the subfloor, and a monumental two-story central staircase with uniformly sized rooms on either side, anchored by the principal salon in the center.[43] Such a “gentlemen” could be found in what way? To use a current phrase, probably via networking of the day: a conversation in Dublin, perhaps, a letter from an acquaintance or relation living in London, chitchat in any number of social interactions, the request for a recommendation from someone higher on the societal chain than yourself, but whom one would like to emulate (the gregarious duke of Ormond, perhaps, whose long and tumultuous career did not detract him from an active interest in the arts, education, and culture in general, and a Col. Eyre being the type of accommodating Protestant that appealed to him).[44] And what might this “gentlemen” have by way of antecedents?

In terms of Eyrecourt, certainly a copy of Sebastiano Serlio’s monumental Architettura was consulted, a seven-volume masterwork lavishly illustrated and carefully organized into specific categories, “On the Five Styles of Buildings,” “On Geometry, On Perspective,” “Extraordinary Book of Doors,” and so on. Serlio began his career as a painter in Bologna but, like so many artisans and craftspeople, wandered about from city to city, spending considerable time in Venice and branching his skill-set into several directions, such as engineering military works, decorating churches, and working on his book(s). Architettura came to the attention of François I, king of France, who invited Serlio to consult on the extravagant hunting palace then being constructed at Fontainebleau, which sealed his reputation and his finances. Architettura was a true ground-breaker in the history of architectural writing, the first printed exemplar of high Renaissance style, written not so much as a history of building trends, but more as a primer to inform, instruct, and guide. Its influence cannot be underestimated. It was published in several editions beginning in 1486, and appeared in Italian, French, Dutch, Flemish, German and, finally, the first four volumes in English, 1611.[45] In Book 7, the parallels between one of Serlio’s sketches and an Eyrecourt fireplace are indisputable.[46]

Serlio was only the beginning. As the seventeenth century progressed and deepened, the circulation of pattern books, practical carpentry guides, volumes of plates and engravings, increased exponentially, along with more philosophical musings on architecture in general, such as Sir Henry Wotton’s important Elements of Architecture Collected … from the Best Authors & Examples, 1624.[47] By the 1700s, British and Irish craftsmen had a plethora of titles to consult, as well as the knowledge and skill of countless foreign workers from whose example their own development could progress. These men travelled widely, from city to city, job site to job site. Those who built Eyrecourt were not “some hedge carpenter(s),” as Lady Morgan referenced in her The Wild Irish Girl, though they were, collectively, just as anonymous.[48]

In determining the provenance of the staircase carvings, which has perplexed art historians for decades, the same questions arise. Who carved the balustrade panels, the flower urns, the set of grotesque heads that overlook the two archways over the first set of risers, the carvings on the raised panels of the newel posts? Were they created on site or ordered from abroad and shipped to Ireland? What tradition or school do they represent? The Knight of Glin, Ireland’s premier authority on such matters, at first suggested Germany, but later Holland or the Lowlands.[49] It is doubtful, in fact, if we will ever know.

There are hints, to be sure. The Town Hall of Amsterdam, completed in 1655, features fifteen years worth of work by the sculptor Artus (Arnold) Quellinus, whose designs were portrayed in elegant engravings by his brother, Hubert, in a folio edition dated 1660. These were immensely popular as reference materials, illustrating decorative flourishes, cascades, and ornaments that both sculptors and wood carvers copied for decades. Quellinus’s work had more impetus on the spread of what is called “Flemish baroque” then that of any other single artist.

Dutch traditions in still-life paintings of flowers, wheat stalks, garlands of plant life, game, and so on, provided considerable inspiration to those working in wood, in particular the spectacular carvings of Grinling Gibbons, who is only the most famous of what were, in fact, a growing number of artisans working in and around London during the great boom of the 1670s. As Charles II, from his days in exile, had considerable familiarity with Holland and France, and less so of Italy, it is not surprising that the initial influx of skilled craftsmen in most of the decorative arts (save plasterers) came from those countries, and were encouraged to do so (as in 1662, with a legislation entitled “An act for encouraging Protestant strangers and others to inhabit Ireland”).[50] That these craftsmen traveled widely once in Great Britain is also indisputable, and in their employments from worksite to worksite experiences were shared, trade secrets observed and copied, skills honed. Inevitably a trickle of such talents reached Ireland, where their services were especially valued as a building resurgence commenced after the Restoration in 1660 that would continue until the Williamite wars began twenty-eight years later. Soldiers turned “gentlemen” such as Eyre began building different sorts of structures, different, that is, to what powerful men like Richard Burke, 4th earl of Clanricard, had built in nearby Portumna just forty years before – a “strong house” to be sure, but one not completely given over to a military purpose. In the words of Henry Hyde, earl of Clarendon and lord lieutenant of Ireland, the goal now were buildings “raised for beauty.”[51]

Certainly the pastoral motifs of Gibbons and his contemporaries multiplied exponentially in the building projects of both the greater and lesser nobility throughout Great Britain. Windows, doorways, mirrors, portraits, and so forth, were commonly surrounded by woodcarvings of laurels, ribbons, flowers and the like, all wrapped around everything from columns to musical instruments. Masters like Gibbons were relentlessly imitated, much to their annoyance it must be assumed, but they were so busy with work, many originating from Christopher Wren’s commission to replace fifty-two of the eighty-seven parish churches in London destroyed by the Great Fire, that prosecution of intellectual theft was no doubt physically impossible.[52] Wren surrounded himself with designers, contractors, planners – the entire panoply of the construction industry – that for many highly skilled and sought for men there was hardly time to think. Gibbons grew rich, and the owners of ateliers of workmen, such as the redoubtable Edward Pearce, who also worked with Wren, dealt with all manner of decorative projects in both stone and wood. The great staircase of Sudbury Hall in Derbyshire, contemporaneous with Eyrecourt’s, gives our best clue yet at to the possible construction mode of Eyrecourt. Pearce evidently did not design or build the outer structure of the staircase; his commission was restricted solely to the balustrade’s paneling, which were the by now customary interweave of acanthus leaves in full floridity, evidently carved in Pearce’s workshop in London, then shipped to the site for installation. Pearce received £112. 15s. 5d for all the panels, two door casings, and miscellaneous “swags” and “festoons.” [53]

The acanthus is a perennial shrub, most diverse and common in the Mediterranean basin. Noted for its spiny, thickly veined leaves, early stonemasons in Greece and Asia Minor appreciated its decorative possibilities as a “drape” or curling form drooping downwards, and carved them into the capital heads of supporting pillars that came to be known by the adjective “Corinthian.” Roman designers expanded the device by adding a volute, or spiral scrolling, from the “Ionic” capital, thereby coming up with what architectural historians call the “Composite” (or “mixed”) order, a device seen everywhere in the western world, even today. The acanthus leaf, with its flowing form and sculptural characteristics, became a favorite of Renaissance, and then baroque woodcarvers in particular, as well as their patrons who looked to the classical world, and particularly Rome, as the fountainhead of art and culture.[38] At Eyrecourt, the acanthus motif is exuberantly displayed in the several panels inserted between the steps themselves and the handrails. These make the military decorations in the balustrade at Ham House in Great Britain, mentioned previously, seem banal by comparison, no matter the skill of carving displayed.

How and why would a Col. John Eyre, or his wife, be inspired by such designs? Or better yet, how would he ever have learned about them? Eyrecourt was reputedly built in the early 1660s, Col. Eyre then a man of probably middle age and entering the prime of his life, both physically and professionally. He was now a person of some consequence, certainly in County Galway and in Dublin, and possibly in London. The great era of classical building in Ireland, generally thought to have commenced under the duke of Ormond in 1680 (the Royal Hospital at Kilmainham) was still two decades into the future, likewise the extraordinary work of the Huguenot wood carver James Tabary and his two brothers, who worked on the exquisite altar piece that graces its chapel. The premier woodcarver of the seventeenth-century generation, Grinling Gibbons, a "myth encrusted figure” according to one art historian,[39] had not even landed in London from Rotterdam after the Great Fire of 1666 to begin his extraordinary career, so in all probability Col. Eyre had never heard of him; nor do we have any proof that Eyre returned to England after his Cromwellian beginnings in Ireland a decade before, during which he might have observed the work of a growing number of artisans, largely Protestant, who were emigrating to London from the continent in search of work or commissions. Possibly the most promising, if most uncertain explanation of Eyrecourt’s origins, might be “word of mouth,” a category ambiguously described by the Irish architectural historian R. Loeber as “less well defined influences.”[40]

Sir Roger Pratt, along with Christopher Wren an important figure in the development of professionalism in the field of British architecture, was known to have written tracts of advice and “principles” to guide both other designer/builders and those who might employ them, though the bulk of these remained unpublished at the time of his death in 1685. His reputation in court circles was considerable, as evinced by his appointment by Charles II to join Wren and Hugh May as commissioners to oversee the reconstruction of fire-ravaged central London in 1666, for which he received a knighthood.[41] In one of his piquant observations, written perhaps to advise country gentlemen who might doubt their own abilities or inclinations when it came to envisioning the construction of a seat, Pratt noted firstly, to “resolve with yourself what house will be answerable to your purse and estate … then if you be not able to handsomely contrive it yourself, get some ingenious gentleman who has seen much of that kind abroad and been somewhat versed in the best authors of Architecture: viz. Palladio, Scamozzi, Serlio etc. to do it for you, and to give you a design of it in paper.”[42] Such shadowy figures as these, i.e. “some ingenious gentlemen,” might have a satchel of drawings, elevations, sketches, or profiles of their own designs to pour over with a potential client, or a booklet of engravings or plates depicting examples from ancient Rome or, perhaps, representations of newly famous buildings, such as the town hall of Amsterdam, begun in 1648. These were ready-made to adapt, copy, or alter as circumstances (or one’s financial circumstances) might allow. It is interesting to note that Pratt was best known for producing buildings that seem, at first glance, remarkably similar to Eyrecourt: hipped roofs, dormer windows, a surround walkway for views, half- windows on the subfloor, and a monumental two-story central staircase with uniformly sized rooms on either side, anchored by the principal salon in the center.[43] Such a “gentlemen” could be found in what way? To use a current phrase, probably via networking of the day: a conversation in Dublin, perhaps, a letter from an acquaintance or relation living in London, chitchat in any number of social interactions, the request for a recommendation from someone higher on the societal chain than yourself, but whom one would like to emulate (the gregarious duke of Ormond, perhaps, whose long and tumultuous career did not detract him from an active interest in the arts, education, and culture in general, and a Col. Eyre being the type of accommodating Protestant that appealed to him).[44] And what might this “gentlemen” have by way of antecedents?

In terms of Eyrecourt, certainly a copy of Sebastiano Serlio’s monumental Architettura was consulted, a seven-volume masterwork lavishly illustrated and carefully organized into specific categories, “On the Five Styles of Buildings,” “On Geometry, On Perspective,” “Extraordinary Book of Doors,” and so on. Serlio began his career as a painter in Bologna but, like so many artisans and craftspeople, wandered about from city to city, spending considerable time in Venice and branching his skill-set into several directions, such as engineering military works, decorating churches, and working on his book(s). Architettura came to the attention of François I, king of France, who invited Serlio to consult on the extravagant hunting palace then being constructed at Fontainebleau, which sealed his reputation and his finances. Architettura was a true ground-breaker in the history of architectural writing, the first printed exemplar of high Renaissance style, written not so much as a history of building trends, but more as a primer to inform, instruct, and guide. Its influence cannot be underestimated. It was published in several editions beginning in 1486, and appeared in Italian, French, Dutch, Flemish, German and, finally, the first four volumes in English, 1611.[45] In Book 7, the parallels between one of Serlio’s sketches and an Eyrecourt fireplace are indisputable.[46]

Serlio was only the beginning. As the seventeenth century progressed and deepened, the circulation of pattern books, practical carpentry guides, volumes of plates and engravings, increased exponentially, along with more philosophical musings on architecture in general, such as Sir Henry Wotton’s important Elements of Architecture Collected … from the Best Authors & Examples, 1624.[47] By the 1700s, British and Irish craftsmen had a plethora of titles to consult, as well as the knowledge and skill of countless foreign workers from whose example their own development could progress. These men travelled widely, from city to city, job site to job site. Those who built Eyrecourt were not “some hedge carpenter(s),” as Lady Morgan referenced in her The Wild Irish Girl, though they were, collectively, just as anonymous.[48]

In determining the provenance of the staircase carvings, which has perplexed art historians for decades, the same questions arise. Who carved the balustrade panels, the flower urns, the set of grotesque heads that overlook the two archways over the first set of risers, the carvings on the raised panels of the newel posts? Were they created on site or ordered from abroad and shipped to Ireland? What tradition or school do they represent? The Knight of Glin, Ireland’s premier authority on such matters, at first suggested Germany, but later Holland or the Lowlands.[49] It is doubtful, in fact, if we will ever know.

There are hints, to be sure. The Town Hall of Amsterdam, completed in 1655, features fifteen years worth of work by the sculptor Artus (Arnold) Quellinus, whose designs were portrayed in elegant engravings by his brother, Hubert, in a folio edition dated 1660. These were immensely popular as reference materials, illustrating decorative flourishes, cascades, and ornaments that both sculptors and wood carvers copied for decades. Quellinus’s work had more impetus on the spread of what is called “Flemish baroque” then that of any other single artist.

Dutch traditions in still-life paintings of flowers, wheat stalks, garlands of plant life, game, and so on, provided considerable inspiration to those working in wood, in particular the spectacular carvings of Grinling Gibbons, who is only the most famous of what were, in fact, a growing number of artisans working in and around London during the great boom of the 1670s. As Charles II, from his days in exile, had considerable familiarity with Holland and France, and less so of Italy, it is not surprising that the initial influx of skilled craftsmen in most of the decorative arts (save plasterers) came from those countries, and were encouraged to do so (as in 1662, with a legislation entitled “An act for encouraging Protestant strangers and others to inhabit Ireland”).[50] That these craftsmen traveled widely once in Great Britain is also indisputable, and in their employments from worksite to worksite experiences were shared, trade secrets observed and copied, skills honed. Inevitably a trickle of such talents reached Ireland, where their services were especially valued as a building resurgence commenced after the Restoration in 1660 that would continue until the Williamite wars began twenty-eight years later. Soldiers turned “gentlemen” such as Eyre began building different sorts of structures, different, that is, to what powerful men like Richard Burke, 4th earl of Clanricard, had built in nearby Portumna just forty years before – a “strong house” to be sure, but one not completely given over to a military purpose. In the words of Henry Hyde, earl of Clarendon and lord lieutenant of Ireland, the goal now were buildings “raised for beauty.”[51]

Certainly the pastoral motifs of Gibbons and his contemporaries multiplied exponentially in the building projects of both the greater and lesser nobility throughout Great Britain. Windows, doorways, mirrors, portraits, and so forth, were commonly surrounded by woodcarvings of laurels, ribbons, flowers and the like, all wrapped around everything from columns to musical instruments. Masters like Gibbons were relentlessly imitated, much to their annoyance it must be assumed, but they were so busy with work, many originating from Christopher Wren’s commission to replace fifty-two of the eighty-seven parish churches in London destroyed by the Great Fire, that prosecution of intellectual theft was no doubt physically impossible.[52] Wren surrounded himself with designers, contractors, planners – the entire panoply of the construction industry – that for many highly skilled and sought for men there was hardly time to think. Gibbons grew rich, and the owners of ateliers of workmen, such as the redoubtable Edward Pearce, who also worked with Wren, dealt with all manner of decorative projects in both stone and wood. The great staircase of Sudbury Hall in Derbyshire, contemporaneous with Eyrecourt’s, gives our best clue yet at to the possible construction mode of Eyrecourt. Pearce evidently did not design or build the outer structure of the staircase; his commission was restricted solely to the balustrade’s paneling, which were the by now customary interweave of acanthus leaves in full floridity, evidently carved in Pearce’s workshop in London, then shipped to the site for installation. Pearce received £112. 15s. 5d for all the panels, two door casings, and miscellaneous “swags” and “festoons.” [53]

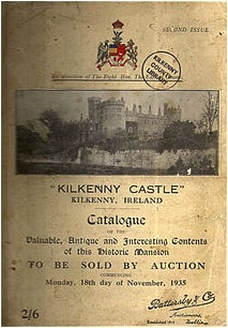

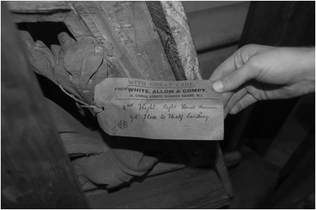

Auction catalogue, Kilkenny Castle, 18 November 1935.

Auction catalogue, Kilkenny Castle, 18 November 1935.